Rockville, Md.

“Who would draw a picture to divide 2/3 by 3/4?” asked Marina Ratner, a professor emerita of mathematics at the University of California at Berkeley, in a .

Ratner meant the question as rhetorical—she’s an adamant opponent of the Common Core State Standards in math and spends the article arguing that they’re making math education in the country worse. Her point was that drawing such a picture is a waste of time and makes the problem overly complex.

However, at a professional development session on the common core I attended last month, held by the Maryland department of education, a small group of middle school math teachers learned how to illustrate these types of equations. And as evidenced by the “oohs” and “ahhs” voiced during the hour-and-a-half-long session, most attendees found it quite illuminating.

Maryland teachers Terry Wheeler and Dawn Caine taught the group four ways to represent division of fractions by fractions—not one of them was the “invert and multiply” rule that all of the adults in the room had been taught.

As I’ve mentioned before, the common core requires more conceptual understanding than most previous state standards. In fact, when asked about the difference between the old and new standards, many teachers have pointed to fractions as an example—they can no longer teach “Don’t ask why, just invert and multiply.” Now they have to help students “make sense of problems,” as the common core’s require. And that’s not always easy to do.

“I’ve been able to divide fractions since I was taught it,” said Caine. “But I was a teacher when I understood how to graphically model what it means.”

Caine and Wheeler showed four models for illustrating division of fractions:

- Area model

- Number line model

- Tape diagram model

- Common denominator model

For the sake of space, I’ll show the number line and common denominator models here. Their entire presentation is (see M106 - Some Middle School Standards Are More Difficult to Interpret and Understand in Mathematics).

Number Line

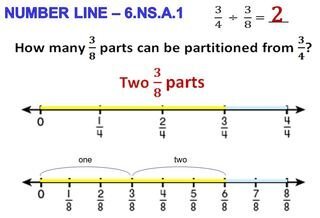

The PD leaders started with division of fractions by whole numbers, and scaffolded from there. But I’ll begin right with division of fractions by fractions (a 6th grade common-core standard). Here’s the Powerpoint slide from their presentation.

The teachers first translated the equation 3/4 divided by 3/8 into words: “How many 3/8 parts can be partitioned from 3/4?” That wording in and of itself was a change for most teachers. Then they showed a number line from 0 to 1, divided into fourths. The yellow line above shows what 3/4 looks like.

Caine explained that the yellow line, 3/4, is the “new whole.” The equation is asking, how many 3/8 parts can fit into that new whole? In order to figure this out, students need to divide the same number line again, this time into eighths. Then they are able to count out the number of 3/8 parts within the yellow line. There are two.

The method does become more complicated with numbers that don’t divide evenly. But the same concept holds true.

Common Denominator

The common denominator model, while not really a picture, demonstrates that the same rules apply to multiplication and division with fractions. It also shows why “invert and multiply” works. (For me, and most of the teachers there, learning this was a true “aha” moment.)

All students have to do is convert the given fractions into fractions with the same denominator. Then they can divide across. Each time they do this, they’ll get a 1 on the bottom (above, 8 divided by 8 equals 1). The fraction in the numerator will simply be the answer.

Caine recommended teachers show their class all four methods, and allow students to choose the one that makes the most sense to them. Eventually, the PD leaders said, students can and should learn the “invert and multiply” rule, to save time with more complicated problems.

“I like for kids to be efficient in math if they understand the concepts below it,” said Caine. “I don’t like shortcuts if they don’t understand the concepts.”

Having looked over the above ways of introducing fractions division, what are your thoughts? Would you prefer to go straight to the algorithm, or start with these alternate, conceptual representations? Or do you think this confirms Ratner’s claim, in the Wall Street Journal, that under the common standards, “simple concepts are made artificially intricate and complex”?