Louisville, Ky.

To find talented children who historically have been overlooked in gifted education, Wheeler Elementary educators are learning to see their students in a new way.

Early one morning this fall, 3rd grade teacher Kristin Finck watched Tiffani Morrison, a gifted teacher in the districtтАЩs Reaching Academic Potential program, give her students a lesson on ocean ecology and conservation and ask students to come up with inventions to protect endangered animals. She circulated quietly, listening to her students excitedly describe armor for sharks and radar to locate floating islands of trash.

тАЬOne of them drew a turtle and talked about how pollution can damage the shell, and she had a robot machine that could clean it,тАЭ Finck said. тАЬAnd it wasnтАЩt a student youтАЩd think would do thatтАФit wasnтАЩt one of our high-performers. ... ItтАЩs just a reminder that gifted and talented covers several different aspects, and itтАЩs not just a black-and-white thing.тАЭ

The number of gifted students identified at the school has risen from 22 when the project started in 2015 to 39 in 2017. Districtwide, more than 9 out of 10 students who have been identified as gifted under the program qualify for free or reduced-price lunch.

ItтАЩs a hopeful sign for Jefferson County, which like many districts has been working to expand the number and diversity of academically gifted children it serves. In a nationally representative survey by the ░─├┼┼▄╣╖┬█╠│ Research Center, 58 percent of gifted educators reported that students in poverty were underrepresented in their programsтАФhigher than the percentage who reported service gaps for students with disabilities.

The best way to do this, experts say, is to test everyone, preferably with more than one kind of test. Jefferson does give every 3rd grader verbal and nonverbal giftedness tests. But itтАЩs not an ultimate solution; the tests are expensive and they may not differentiate a student who comes to school with deep background knowledge and lots of educational advantages from one who may be less advantaged but can actually learn faster.

In the ░─├┼┼▄╣╖┬█╠│ survey, a little more than 1 in 4 gifted educators reported that their districts screen all students for gifted services once in elementary school, but nearly 3 in 4 said they used teacher referrals to identify potentially advanced students. ThatтАЩs why Jefferson County, Seminole County, Fla., and a handful of other districts are taking a different approach to improving gifted identification.

In addition to traditional gifted screening tests, educators in the programs use portfolios of student work and a series of тАЬresponse lessons.тАЭ By giving a lesson on an unusual topicтАФwhich even economically advantaged students likely havenтАЩt seenтАФteachers can compensate some for differences in studentsтАЩ background knowledge, and focus instead on how quickly students learn something new and how creatively they can think about it.

In a response lesson, a trained gifted-education teacher presents the class with a series of lessons in a variety of subjects over the course of a few weeks. Each lesson has been calibrated to encourage creative thinking and problem-solving, and over time, studentsтАЩ answers have been studied to identify the quality, intensity, and frequency of studentsтАЩ ahead-of-the-curve responses.

Response Lessons in Practice

Teachers also learn to create their own response lessons, which could help make the model more sustainable for resource-strapped schools, according to Kathie Anderson, the gifted education coordinator for the Kentucky state education agency.

тАЬI would think the response lessons would be less expensive, because you could take almost any book to create a prompt for students and then look at the results,тАЭ Anderson said. тАЬIt would use resources [districts] already have on hand, so I donтАЩt think it would cost as much as, maybe, getting the Williams [scale] or the Torrance creativity tests, which cost about $8 to $10 a pop.тАЭ

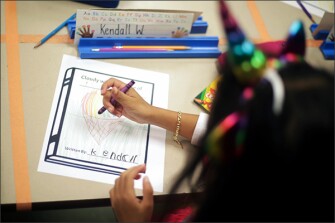

The 660-student, K-5 Wheeler Elementary has about 45 percent of students from low-income backgrounds and is one of five in Jefferson County testing the program. One day this fall, Morrison sat beside a projection of George SeurratтАЩs famous painting of a beach scene, тАЬA Sunday on La Grande Jatte,тАЭ with a little crowd of 1st graders at her feet. She explained pointillismтАФa painting method in which dots of paint create patterns and shapesтАФand highlighted the dots in the painting, before reading Peter H. ReynoldsтАЩs тАЬThe Dot,тАЭ about a little girl learning to paint.

тАЬJust make a mark and see where it takes you,тАЭ she read.

The group discussed concepts that might be considered advanced for 1st graders: positive and negative space, randomness, connections between pointilism and pixels on a screen, and the details seen close and far away. Then Morrison dismissed students with handfuls of green and orange sticker-dots to spread randomly on a paper and hand over to a classmate, who used the page to make a picture.

тАЬYouтАЩre going to use your imagination, and youтАЩre also going to write me a sentence so I can see in your brain what youтАЩre trying to show,тАЭ Morrison said.

ThereтАЩs a lot to see in each of these pictures. How well does the student understand randomness? (Some immediately make a grid, or try to draw a picture using the stickers.) How well do they remember the directions and how to interact with their peers? How imaginative are their pictures?

Most students simply try to connect all the dots into a pattern and then color them in, Morrison said. She was looking for unusual thinking.

Evan turned his dots into a Christmas scene, with himself dancing in a neon snowstorm and others decorating a tree. Ashtyn drew a rainbow-striped flagтАФperhaps not so unusual, except that she curved it from one dot to the next to create a ripple effect.

тАЬThatтАЩs surprising,тАЭ said Principal Penny Espinosa, noting that the girl is a struggling reader and hasnтАЩt тАЬstood outтАЭ academically in other subjects. She paused, watching the little girl color. тАЬYou know, itтАЩs neat to see their creative thinking; I donтАЩt know that we give them enough opportunities to do things like that,тАЭ Espinosa said.

Guiding Teachers

Teacher professional development forms the core of the programsтАЩ identification strategy.

Seminole County, Fla., public schools partnered with the University of Central Florida to deepen professional development for teachers on how to spot students with high potential.

тАЬWe have spent a lot of time working on the characteristics of gifted students, but also how [those characteristics] can manifest with students who are coming from diverse backgrounds,тАЭ said Jeannette Lukens, the director of Project ELEVATE, in Seminole County schools. тАЬWeтАЩve spent quite a bit of time addressing myths, misconceptions, stereotypes of those learners.тАЭ

For example, Lukens said teachers often discount leadership or creative thinking when it comes in the form of playground pranks. тАЬFor example, a student influences students to behavior that may not be appropriate on the playground. ... but [the student] really has leadership skills that show theyтАЩre able to get students on board and keep them engaged.тАЭ

Since implementing ELEVATE, the districtтАЩs overall gifted population has risen 44 percent, to more than 2,300. Low-income students have increased from 22 percent to 38 percent. The program has also become more diverse, with 175 additional black students, 310 more Hispanic students, and 75 more English-learners identified as gifted.

Lukens said the district is developing case studies based on some of the students and using virtual simulations to help teachers understand how to spot students with highтАФbut sometimes hiddenтАФpotential.