Corrected: The legend in the map below has been corrected online.

Grace, a tiny 3rd grader with long black hair and wide-set eyes, peers over her teacherŌĆÖs shoulder at the results of the oral-fluency test sheŌĆÖs just finished, which appear on the screen of a hand-held computer as a tiny green triangle up in the right-hand corner.

ŌĆ£So, you read 147 words,ŌĆØ says teacher Laura Wallin of Mountainview Elementary School. She taps the screen and another graph pops up that plots GraceŌĆÖs reading fluency over time. ŌĆ£At the beginning of the year, you started out at 92 words per minute, then 105. What do you think is helping you the most?ŌĆØ

- ŌĆó Palm Readers:

Teachers in a rural New Mexico district use hand-held computers to assess studentsŌĆÖ reading progress and target instruction accordingly. - ŌĆó Critical Thinking:

Schools in Boston are gaining insight into their studentsŌĆÖ thought processes through a locally developed reading-assessment system.

MAY 2

- ŌĆó New Math:

Teachers in a Texas school have shelved some of their math textbooks and turned to an online curriculum and formative-assessment resource instead.

MAY 9

- ŌĆó Teacher Training:

A California center is using formative assessment to help beginning teachers reflect on and improve their own work and that of their students.

MAY 16

ŌĆ£When we practice reading to our partners, it helps me,ŌĆØ Grace says, citing times when her partner told her not to skip words as she read out loud. ŌĆ£And it helps me when we have this time to go over it; it helps me know what to work on.ŌĆØ

Similar encounters between teachers and students occur on a regular basis in the five elementary schools in this far-flung rural school system, which is about the size of Rhode Island and enrolls some 4,000 students in kindergarten through 12th grade. But that wasnŌĆÖt always the case.

Before the school system began using the Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills, or DIBELS, assessments, the district had no common reading program in the early grades and no way of regularly checking studentsŌĆÖ progress, district officials say.

ŌĆ£There were as many different programs going on as there were teachers,ŌĆØ recalled Joshua S. McCleave, the principal of the 330-student South Mountain Elementary School, another school in the Moriarty school district.

Three years ago, with the help of a federal Reading First grant, the district began using the DIBELS assessments across its elementary schools along with the mCLASS: DIBELS assessment and reporting system. The districtŌĆÖs experience helps illustrate the ways educators can use one popular assessment tool to better inform and shape classroom teaching and learningŌĆöa concept often labeled ŌĆ£formative assessment.ŌĆØ

The assessments, developed by researchers at the University of Oregon, include thrice-yearly benchmark tests to help screen and group students, as well as more-frequent, one-minute ŌĆ£progress monitoringŌĆØ measures. Those measures track youngstersŌĆÖ responses to instruction on a particular literacy skill, such as initial sound fluency, phoneme segmentation, reading of nonsense words, or oral-reading fluency. As early as kindergarten, the probes identify children considered at risk for not learning to read.

Using the mCLASS: DIBELS assessment system, developed by Wireless Generation, a for-profit company based in New York City, teachers are able to give and record DIBELS results on hand-held computers and get instant feedback. Teachers can then upload the results to the Wireless Generation Web site to track class, school, and district performance over time using online reports.

Naomi Hupert, a senior research associate with the Boston-based Education Development Center, which is evaluating New MexicoŌĆÖs Reading First program, said the approach lets teachers collect and instantly access their own data without feeling they are just ŌĆ£administering something that was supposed to be sent off to the state or the district.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£The greatest advantage we see,ŌĆØ Ms. Hupert said, ŌĆ£is that teachers, for the first time, felt like the data was for their own purpose.ŌĆØ

Flexible Reading Groups

Nationally, about 100,000 teachers in 49 states now use Wireless GenerationŌĆÖs software to conduct and analyze DIBELS assessments with some 2.3 million students.

Before adopting the program, every K-3 teacher in the participating Moriarty schools agreed to a list of ŌĆ£non-negotiables.ŌĆØ

The list includes an uninterrupted 90-minute reading block for students using the Harcourt Trophies reading program. During that time, students are flexibly grouped based on their needs, with the groups shifting regularly, depending on test results.

Schools also carve out additional intervention time outside the reading block: 30 minutes for all students and 60 minutes for those who need the most intensive help. In the three elementary schools receiving Reading First grants, the latter may include individual or small-group instruction from a reading coach or specialist.

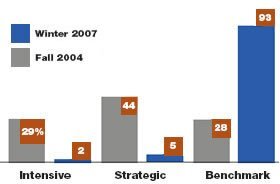

When the Moriarty district first introduced computer-based reading tests, 29 percent of kindergartners scored at the lowest, or ŌĆ£intensiveŌĆØ level. That figure fell to 2 percent this year, while students testing at the top level, ŌĆ£benchmark,ŌĆØ rose from 28 percent to 93 percent.

ŌĆ£We were truly asking teachers to make paradigm shifts, and in asking them to do that, we were asking some of them to change the way they had been teaching for 20 years,ŌĆØ said Laura E. Moffitt, the coordinator of federal programs for the school district and the driving force behind its reading efforts.

Teachers at every school meet at least once a month, by grade level, to analyze DIBELS and other data, adjust instructional groupings, and decide what to do next to support individual children. Teachers monitor childrenŌĆÖs progress using DIBELS subtests as often as once a week, or at least once every six weeks, depending on whether youngsters perform at the ŌĆ£intensiveŌĆØ (high risk), ŌĆ£strategicŌĆØ (some risk), or ŌĆ£benchmarkŌĆØ (low risk) level on the assessments.

ŌĆ£If we notice a child has fallen below their target score, we talk about it then,ŌĆØ explained Tonya S. Newton, the reading coach at Mountainview Elementary School. ŌĆ£What IŌĆÖm trying to do is get the teachers to come up with the interventions during the meeting, because if you wait three weeks for a child, thatŌĆÖs a lot of time lost.ŌĆØ

Moriarty schools also share the information generated by the assessments with parents during back-to-school nights and parent-teacher conferences. And they provide homework packets and suggestions for parents to work with their youngsters on specific skills.

ŌĆśSo Much More InformationŌĆÖ

A recent analysis by Wireless Generation, based on results from roughly 200,000 students in nearly 1,300 schools in 31 states, found that frequent progress monitoringŌĆöabout once a weekŌĆöyielded the greatest reading gains for students at all reading levels, as measured by changes on the benchmark exams.

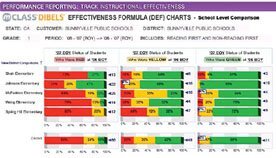

The mCLASS: DIBELS system in use in Moriarty provides Web-based reports on individual students, such as the one below, and reports for whole schools and districts.

The chart below uses colored bars to show changes in studentsŌĆÖ reading ŌĆ£riskŌĆØ status over the course of a school year.

Ms. Newton, whoŌĆÖs been teaching for 17 years, is a passionate defender of the approach, based on her own experiences. ŌĆ£When I taught 6th grade, I always had that lower reading group, and it just tore me up,ŌĆØ she said, ŌĆ£because they couldnŌĆÖt read the textbooks, and I didnŌĆÖt know how to fix it.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£I think this,ŌĆØ she added, pointing to the data-covered walls of her office, ŌĆ£will catch some of those kids.ŌĆØ

At Moriarty Elementary School, for example, 2nd grade teachers began a grade-level meeting by looking at the performance of pupils who had recently moved from one reading group to another because of their DIBELS scores, to see if they were continuing to make progress. They also reviewed the work of two children who had temporarily been moved from the ŌĆ£strategicŌĆØ to the ŌĆ£intensiveŌĆØ group so they could get more help.

Each school decides how to organize the instructional groups during the morning reading block. But generally, the schools use a ŌĆ£walk to readŌĆØ model, in which students leave their homeroom teachers to go to another classroom composed of students at a similar reading level. Because students change reading groups frequently, based on new data, all of the teachers get to know every child.

ŌĆśMakes You More AwareŌĆÖ

During the meeting, teachers also pulled out detailed summaries for individual students to look at where they were struggling, and discussed what types of activities might address their needs.

ŌĆ£I think it makes you more aware of areas you need to delve into,ŌĆØ said 2nd grade teacher Carlotta Ballard. ŌĆ£Sometimes, youŌĆÖre so used to looking at the big picture.ŌĆØ

ŌĆ£Plus, we all have different expertise,ŌĆØ added teacher Rebecca Cavasos, ŌĆ£and so weŌĆÖre able to go to one another.ŌĆØ

Typically, teachers will look for trends across at least three different progress-monitoring reports before deciding to move a childŌĆÖs reading group. TheyŌĆÖll also look at class work, homework, and results from other assessments, such as the Teacher Primary Reading Inventory and the tests that accompany the Harcourt Trophies series. Sometimes, teachers will call an emergency meeting if they feel they need to make a decision about a child right away.

Although teachers initially gave DIBELS as a paper-and-pencil assessment, many say it was too cumbersome to use regularly. Now, said 1st grade teacher Jaree Whitworth of the 410-student Edgewood Elementary School, ŌĆ£I just feel like I get so much more information.ŌĆØ

The Web-based graphics help. ColorsŌĆöred, yellow, and greenŌĆöhighlight whether studentsŌĆÖ performance on any particular subtest is at the ŌĆ£intensive,ŌĆØ ŌĆ£strategic,ŌĆØ or ŌĆ£benchmarkŌĆØ level. A little running man across the bottom of some screens shows students where they are in relation to end-of-year goals. And scatter plots highlight whether each progress-monitoring result puts a youngster at, above, or below his or her target performance.

Larry Berger, the founder and chief executive officer of Wireless Generation, said use of the hand-held devices saves teachers the equivalent of four or five instructional days per year. ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs pretty rare in education that anybody automates something that teachers actually do all day and thereby saves them some time,ŌĆØ he said.

Sustainability an Issue

In Tammy SatterfieldŌĆÖs ŌĆ£strategicŌĆØ reading group at Mountainview Elementary, about a dozen 1st graders do jumping jacks as they recite the vowel sounds that theyŌĆÖve been working on from the dayŌĆÖs word chart. Once theyŌĆÖre seated, Ms. Satterfield points to the word wall and says: ŌĆ£We have some new words. Raise your hand if you can tell me some of our new words.ŌĆØ

Soon, the class moves on to breaking up words into their sounds and then sliding them back together to form whole words. ŌĆ£Why do I do this every day?ŌĆØ asks Ms. Satterfield. ŌĆ£Because it helps you read your words,ŌĆØ the pupils chant back. ŌĆ£Is it our only strategy?ŌĆØ the teacher asks. ŌĆ£No,ŌĆØ they chorus.

Later, the teacher acknowledged that sheŌĆÖs putting in more hours planning instruction, but says itŌĆÖs worth it. ŌĆ£Before, you just hoped you were getting to everyone,ŌĆØ she said, ŌĆ£but with the progress monitoring and DIBELS, itŌĆÖs less likely that children will fall behind because youŌĆÖre in contact with them all the time. ItŌĆÖs such an interactive program.ŌĆØ

When 1st grade teachers discovered, for example, that most children were having trouble with oral fluency on the midyear assessments, they added a program during the afternoon intervention time called ŌĆ£Reading NaturallyŌĆØ that focuses on fluency. They also began frequent monitoring of 1st gradersŌĆÖ oral fluency earlier in the year.

In the fall of 2004, when the program began, 29 percent of kindergartners in the district were reading at the intensive level and 28 percent at the benchmark level on the DIBELS benchmark assessments. By this winter, only 2 percent of kindergartners performed at the intensive level, while 93 percent read at the benchmark level.

About 70 percent of 1st and 2nd graders now read at the benchmark level on the assessments. And special education referrals in the Moriarty district have dropped as regular education teachers have felt more comfortable addressing individual youngstersŌĆÖ needs. Both the special and bilingual education teachers take part in grade-level meetings at each school.

But the biggest change, according to teachers and principals, may be the responsibility that educators now feel for students other than their own. ŌĆ£It becomes a way of creating a community,ŌĆØ observed Ms. Hupert of the Education Development Center, ŌĆ£where thereŌĆÖs a sense that every studentŌĆÖs reading development is the responsibility of every teacher.ŌĆØ

Yet Moriarty educators admit that challenges remain, particularly in figuring out specific strategies or activities based on the data.

ŌĆ£DIBELS is a screen,ŌĆØ Ms. Moffitt noted. ŌĆ£It doesnŌĆÖt tell you how to change your instructional strategies. Pushing that is where we are now.ŌĆØ

District officials also worry about how to sustain the program once federal Reading First money goes away. The district has put together a working group to look at the issue of sustainability and make recommendations.

For many educators here, though, thereŌĆÖs no going back.

ŌĆ£We used to say, ŌĆśOh, that child is a late bloomer or developmentally not ready,ŌĆÖ ŌĆØ said Principal Julie C. Roark of Edgewood Elementary School. ŌĆ£Now, itŌĆÖs more about what else can we do, what else can we try? You donŌĆÖt accept that children are just not going to get it.ŌĆØ