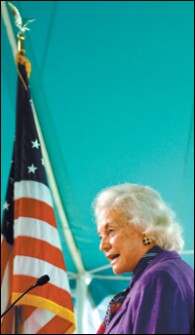

Retiring Justice Sandra Day O’Connor of the U.S. Supreme Court will leave a legacy of influence in decisions affecting public education over the past 24 years.

See the related item,

The first woman on the nation’s highest court, Justice O’Connor, 75, cast the pivotal votes that completed the high court’s majorities on major decisions on private school vouchers, religion in the public schools, affirmative action in college admissions, and sex discrimination in education. The court released her July 1 letter to President Bush in which she informed him that she plans to step down upon the confirmation of a successor.

Though viewed variously as a moderate or a conservative, Justice O’Connor has been renowned for crafting subtle legal opinions that broadened the middle ground on divisive issues.

“It’s a tremendous loss for the nation—it may be the end of moderation on the court,” said Charles C. Haynes, a senior scholar at the Arlington, Va., office of the Nashville, Tenn.-based First Amendment Center, a nonprofit organization that advocates protection of the constitutional rights under that amendment. “She was, in my view, a thoughtful, wise, and careful voice of moderation.”

Mr. Haynes said that although the justice was criticized over the years for “parsing each case and not offering enough of a broad vision, I think her broad vision was how are we going to live and work together across our differences.”

“She helped us to do that by taking these issues case by case,” he said.

Julie Underwood, the general counsel of the National School Boards Association, in Alexandria, Va., said that proof of both her centrism and influence is that, by Ms. Underwood’s count over the past six years, Justice O’Connor was part of more Supreme Court majorities than any other justice.

Clint Bolick, the president and general counsel of the Alliance for School Choice, a Phoenix-based organization that pushes for school voucher programs nationally, said that Justice O’Connor was a “consensus builder” who nonetheless took principled positions on federalism and liberty.

“Generally, she sided with the state sovereignty over federal power and with the individual over government power of any type,” Mr. Bolick said.

‘One Nation’

Justice O’Connor often relied on the facts of a case to steer other justices toward the court’s philosophical midstream, and she also laid out issues in practical ways for educators.

An example is the court’s 1990 decision in Board of Education of the Westside Community Schools v. Mergens, in which an 8-1 majority concluded that the 1984 federal Equal Access Act, which was intended to open public high schools to student prayer groups, did not violate the First Amendment’s prohibition against a government establishment of religion.

In a plurality opinion in Mergens, Justice O’Connor wrote: “There is a crucial difference between government speech endorsing religion, which the establishment clause forbids, and private speech endorsing religion, which the free-speech and free-exercise clauses protect.”

Her distinction between government speech about religion, which cannot be an endorsement, and protected private or student speech is “very helpful … for anyone in public education,” said Mr. Haynes.

“That framing of how the First Amendment ought to work in public schools,” he said, “really gives guidance on many issues that administrators and teachers struggle with.”

On many other important education cases, Justice O’Connor was indeed the swing vote for a narrow majority.

In Zelman v. Simmons-Harris, she was the fifth vote in the 2002 decision that upheld the inclusion of religious schools in the state of Ohio’s school voucher program for Cleveland children. Her concurring opinion cast the court’s upholding of the voucher program as not “a dramatic break from the past.”

In Grutter v. Bollinger and Gratz v. Bollinger, a pair of cases dealing with the University of Michigan’s consideration of race in its undergraduate and law school admissions, decided in July 2003, Justice O’Connor wrote the majority opinion in Grutter and joined the majority in Gratz. Together, the rulings upheld the consideration of race in higher education admissions as long as the process involves individualized review of applicants. Again, Justice O’Connor was the pivotal vote in the 5-4 decisions as she endorsed the diversity rationale for affirmative action.

“Effective participation by members of all racial and ethnic groups in the civic life of our nation is essential if the dream of one nation, indivisible, is to be realized,” she wrote in Grutter.

Justice O’Connor has been influential—and again the fifth vote—in several cases in recent years addressing Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, which prohibits sex discrimination in schools that receive federal funds.

In March, she wrote the majority opinion in Jackson v. Birmingham Board of Education, a 5-4 ruling that a high school girls’ basketball coach could sue his district for alleged retaliation after he complained about inequitable treatment of his female athletes.

Sex-Harassment Cases

And she wrote the majority opinions in two 5-4 decisions in the late 1990s on how schools should handle sexual harassment of students under Title IX.

In 1998, in Gebser v. Lago Vista Independent School District, her opinion laid out for districts guidance on how to avoid liability for sexual harassment of students by teachers. The court’s more conservative members joined her in that opinion. The next year, in Davis v. Monroe County Board of Education, she voted with the court’s more liberal members and wrote an opinion that said districts could be held liable for student-on-student harassment.

Justice O’Connor was not always in the majority, of course. In 1995, in Vernonia School District v. Acton, she dissented in a 6-3 ruling that upheld drug testing of student-athletes.

“It cannot be too often stated that the greatest threats to our constitutional freedoms come in times of crisis,” she wrote, referring to growing concerns about drug abuse.

Since Justice O’Connor’s announcement, advocates of many stripes have been gearing up for what is expected to be an epic political battle over her successor that needs only President Bush’s choice of a nominee, which could come as soon as this week, to enter full swing.