In an unusual step for a school district, New York City has assigned letter grades to its public schools, prompting a debate in the nationŌĆÖs largest school system about whether the ratings represent a reliable gauge of school quality.

Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg and Schools Chancellor Joel I. Klein in a high-profile announcement at a Manhattan elementary school. Of the 1,224 schools graded, 23 percent received AŌĆÖs, 38 percent got BŌĆÖs, and 25 percent got CŌĆÖs. Eight percent received DŌĆÖs, and 4 percent got FŌĆÖs. More than 150 schools have not been graded yet because they havenŌĆÖt been open long enough or their data were still under review. The cityŌĆÖs 60 charter schools did not administer the survey that forms part of the grade.

The grades are part of New York CityŌĆÖs effort to improve its schools by expanding the authority it gives school principals, and how it makes them answer for their studentsŌĆÖ performance. The grades will be factored into such decisions as whether principals will keep their jobs, a signal Mayor Bloomberg said was a ŌĆ£wake-up callŌĆØ for school staff members.

Schools that got AŌĆÖs and performed well in ŌĆ£school quality reviewsŌĆØ conducted last year by outside teams can get extra money if they agree to serve as ŌĆ£demonstration sitesŌĆØ for other schools. Those that received DŌĆÖs or FŌĆÖs must detail in writing how they plan to improve. D and F schools that also fared poorly in the quality reviews could be closed or have their staffs changed. Students in F schools will be permitted to transfer, though city officials said they did not expect huge numbers to do so.

Some states, such as Florida, assign letter grades to schools as part of their accountability systems. But experts said they knew of no other large school districts that do so, and no others that have created their own accountability systems.

New York City takes a ŌĆ£value addedŌĆØ approach to its ratings, emphasizing student test-score progress over time much more than a single yearŌĆÖs test scores. Fifty-five percent of a schoolŌĆÖs grade is based on how much each student improves his or her scores on state reading and mathematics tests.

Another 30 percent derives from studentsŌĆÖ scores on the most recent tests. The remaining 15 percent relies on parent, teacher, and student surveys gauging school ŌĆ£environmentŌĆØ factors, including safety and academic expectations.

Highs and Lows

The release of school grades by the 1.1 million-student district sparked debate over their meaning. One of the most frequent criticisms was that some schoolsŌĆÖ grades did not seem to jibe with their performance on state tests.

What does this grade mean? Schools are assigned letter grades based on their overall progress-report scores. Schools that get AŌĆÖs and BŌĆÖs are eligible for rewards. Schools that get DŌĆÖs and FŌĆÖs, or three CŌĆÖs in a row, face consequences.

How did this school perform?

ŌĆó This schoolŌĆÖs overall score for 2006ŌĆō07 is 35.1.

ŌĆó This score places the school in the 8.3 percentile of all middle schools citywide (i.e., 8.3 percent of those schools scored lower than this school).

ŌĆó This schoolŌĆÖs target score for 2007ŌĆō08 is 52.6.

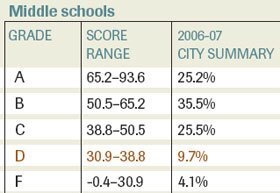

How scores translate to grades:

ŌĆó Schools receive letter grades based on their overall scores.

ŌĆó Schools with overall scores between 30.9 and 38.8 receive a letter grade of D.

ŌĆó 9.7% of schools earned a D in 2006ŌĆō07.

Quality-Review Score

This schoolŌĆÖs 2006ŌĆō07 quality-review score is P. To see a schoolŌĆÖs quality-review report, locate the school at , click ŌĆ£statistics,ŌĆØ and scroll down to quality-review report.

2006-07 State Accountability Status

Based on its 2005-06 performance, this school is ŌĆ£in good standing.ŌĆØ This measure, determined by New York state as part of the federal No Child Left Behind Act, is not a factor in the progress-report grade.

SOURCE: New York City Department of Education

ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖve got high-performing schools that got low grades, low-performing schools that got high grades,ŌĆØ said Tim Johnson, the president of a local education council in Manhattan. ŌĆ£It has a bit of an Alice-in-Wonderland quality about it.ŌĆØ

His own daughterŌĆÖs school, Intermediate School 289 in Manhattan, recently won a prestigious blue ribbon from the U.S. Department of Education. Eighty-three percent of its students showed proficiency on state reading tests, and 85 percent did so on state math tests. But it earned a D under the cityŌĆÖs rating system, largely because its students had not improved sufficiently over their previous yearŌĆÖs scores.

ŌĆ£Our principal should be teaching other principals, not being slapped for not making progress,ŌĆØ Mr. Johnson said.

Mayor Bloomberg saw the results as an opportunity for improvement and a truer judgment of school quality.

ŌĆ£Across the board, these progress reports have challenged our perception about individual schools. And thatŌĆÖs a very positive thing,ŌĆØ he said at the Nov. 5 press conference. ŌĆ£We should be asking ourselves why some of the schools we thought were doing well arenŌĆÖt serving students as effectively as other, similar schools. And we should be asking ourselves how to motivate even very good schools to do better.ŌĆØ

Margaret Goertz, a co-director of the Consortium for Policy Research in Education, based at the University of Pennsylvania, in Philadelphia, commended the city for examining multiple measures of school performance. But she expressed worry about the potential confusion of two appraisal systems, citing the requirements of the federal No Child Left Behind Act.

ŌĆ£When you have different factors than under NCLB, itŌĆÖs going to lead to different grades,ŌĆØ Ms. Goertz said. ŌĆ£If those things arenŌĆÖt coordinated in some way, and youŌĆÖre a building principal or a parent, trying to figure out if a school is good, youŌĆÖre getting very mixed messages.ŌĆØ

Andrew Jacob, a spokesman for the city department of education, said the grading system complements the method used under the almost 6-year-old federal law because it puts more weight on how well a school helps its students improve.

ŌĆ£A lot of schools think they get recognition they didnŌĆÖt get under NCLB,ŌĆØ he said.

The union representing the cityŌĆÖs principals is concerned about the accuracy of the data used in the school grades, and the groupings created to compare schools with similar schools. It asked its members to report problems, and has refrained from endorsing the grades until it can analyze the data and results.

ŌĆ£The ramifications are too great, especially for students in schools that may be mislabeled and the people whose jobs may be on the line,ŌĆØ Ernest A. Logan, the president of the Council of School Supervisors and Administrators, told members in an e-mail the day the grades were released.

The United Federation of Teachers, the cityŌĆÖs teachersŌĆÖ union, called for schools to be judged less by standardized tests and more by additional factors such as class size and access to college-level coursework.

ŌĆ£There is something wrong with the design of an accountability system when schools that have an established track record of solid performance are stigmatized by subpar grades,ŌĆØ Randi Weingarten, the president of the American Federation of Teachers affiliate, said in a statement.