An increase in teacher hiring in recent years has led some observers to posit a link to the waves of pink slips districts are now sending across the country.

Thus far, hiring patterns have not been widely studied as part of the current discussion about layoffs. But national data from the U.S. Department of Education and from the National Education AssociationŌĆÖs annual show that between the 1999-2000 and the 2007-08 school years the teacher force grew at more than double the rate of K-12 student enrollments.

ŌĆ£With accountability and No Child Left Behind, there was increased pressure to raise results, and districts and states responded by adding adults,ŌĆØ said Marguerite Roza, a scholar who has district spending patterns and now serves as a senior economic and data adviser for the Seattle-based Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. ŌĆ£That was the dominant reform model of the last decade.ŌĆØ

Hiring teachers to reduce class sizes remains a perennially popular initiative, but other trends also seem to be in play, too. Districts have begun to experiment with full-time, out-of-class positions for teacher leaders, mentors, and instructional ŌĆ£coaches.ŌĆØ

Although it is difficult to quantify the number of such positions, they are typically drawn from the ranks of classroom teachers, thus necessitating the hiring of replacements.

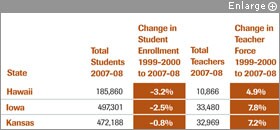

Between 1999-2000 and 2007-08, 14 states brought on new teachers even as student enrollments fell.

SOURCE: National Center for Education Sciences

EPE Research Associate Holly Kosiewicz contributed to this chart.

The equation is a simple one. Districts brought more educators onto the rolls in better budget times. Now, with 80 percent or more of the typical districtŌĆÖs budget caught up in salaries, they may be forced to cut back on some of those positions.

The president of the 3.2 million-member National Education Association, Dennis Van Roekel, acknowledged that districts have added teachers to the rolls to reduce class sizes and to staff initiatives tailored to specific populations, such as students with disabilities. But often, he said, districts have pursued such policies because of perceived needs. Research shows that smaller class sizes in early grades benefit minority students, for example.

He discounted the idea that the policies might be linked to the slew of layoffs.

ŌĆ£I donŌĆÖt think it could ever be attributed to that,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£I just canŌĆÖt imagine any district bringing on more educators than they need.ŌĆØ

Singular Drop

In a recent analysis, Ms. Roza found that the recession caused, in 2009-10, what is only the second decrease in the size of the education labor force since 1993.

According to the NEAŌĆÖs annual ŌĆ£Rankings & EstimatesŌĆØ report, from 1999-2000 to 2007-08, student enrollment increased from 46.6 million to 48.9 million, an increase of about 5 percent. The number of K-12 classroom teachers during that time period rose from 2.89 million to 3.2 million, an increase of 11 percent. Figures over the same time period from the National Center for Education StatisticsŌĆÖ confirm the pattern.

In sum, the hiring of new teachers does not appear to have been offset by attrition or retirements, despite warnings of a wave of baby boomer teacher retirements. In fact, according to the national Common Core data, more than a dozen states have added teachers to the rolls even as their student enrollment declined overall.

Related story: ŌĆ£Congress Urged to Tie Aid in Jobs Bill to Elimination of Seniority-Based Firing,ŌĆØ May 18, 2010.

The reasons underpinning the continued hiring are not clear from the data. But researchers who study human-capital issues suggest several possibilities. While federal funding for class-size reduction waned after 2001, they noted, new types of staffing arrangements have sprung up, including efforts to promote full-time teachers into coaching positions. In those roles, they observe other teachers and provide feedback, help teachers integrate content-specific pedagogical techniques, provide mentoring, or model practices.

Schools have also added more specialists in English-language instruction, special education, and intervention programs.

ŌĆ£TheyŌĆÖve definitely proliferated over the past decade,ŌĆØ said Morgaen L. Donaldson, an assistant professor of education at the University of ConnecticutŌĆÖs Neag School of Education, in Storrs.

Such new roles have also been driven by districtsŌĆÖ efforts to move professional development into schools and make it more relevant rather than sending teachers to workshops.

ŌĆ£My shorthand description, when students ask me what I do, is that IŌĆÖm the teacher for the teachers,ŌĆØ said Gail V. Ritchie, an instructional coach at Centre Ridge Elementary School in Fairfax County, Va. ŌĆ£What worked [in instruction] 10 years ago, even last year, is not necessarily going to work this year.ŌĆØ

The 173,000-student district has a five-year-old coaching program.

Curricular changes have played a role, too. The federal Reading First program, financed from 2002 through 2008, led to an expansion of reading coaches to help teachers with so-called scientifically based instructional techniques, for instance.

It is difficult to determine from the national data set how many such positions may have been created. In both the IES and the NEA data collections, state officials determine whether to classify teachers who serve in coaching roles as ŌĆ£classroom teacherŌĆØ or in another category such as ŌĆ£instructional aide,ŌĆØ according to analysts from the agency and the union.

Kicking the Can?

What is clear, though, is that current teaching positions of all kinds are now in jeopardy.

The actual number of layoffs will depend on whether districts and teachersŌĆÖ unions can agree to wage or benefits concessions or whether districts use furloughs to balance the budget. Estimates of layoff numbers have run as high as 275,000, with half of them teachers.

Avoiding such situations in the future, Ms. Roza said, will require districts to learn how to budget differently. ŌĆ£Districts tend to think of everything in terms of fixed costs,ŌĆØ she said. ŌĆ£Stabilizing a budget would mean that a smaller share of the budget would be tied to committed or escalating costs,ŌĆØ such as salaries.

Some analysts contend that the up-to-$100 billion in education dollars in the federal economic-stimulus legislation, most of it pushed out through formula to states and districts, has only exacerbated the problem. Andy Smarick, an adjunct fellow at the American Enterprise Institute who has studied the economic-stimulus bill, contends that it absolved districts of having to make tough decisions.

ŌĆ£They could have taken the last year to figure out how to resolve these long-term structural issues, to say, ŌĆśLetŌĆÖs look at all of our contracts, letŌĆÖs consider online learning,ŌĆÖ ŌĆØ Mr. Smarick said. ŌĆ£But instead, what they mostly did was preserve existing jobs and programs.ŌĆØ

But another expert noted that state and local mandates have effectively reduced districtsŌĆÖ ability to make careful hiring and layoff decisions.

ŌĆ£School districts are at the end of the trolley line when it comes to budget processes and are left making decisions that are characterized by immediacy,ŌĆØ said Margaret Gaston, the president of the Santa Cruz, Calif.-based Center for the Future of Teaching and Learning, a nonprofit that tracks teacher trends in the Golden State.

ŌĆ£Labor markets are regional, and yet districts are often locked into remedies that are in [state] code, like class-size reduction,ŌĆØ she continued. ŌĆ£We need to establish more flexible incentive programs for school districts rather than lock them down in ways that, in times of crisis, exacerbate the problem.ŌĆØ

Local Decisions

As the notices continue and districts begin to finalize cuts, some advocates worry about what theyŌĆÖll mean for new staffing models.

After all, since layoffs disproportionately affect novices, there will presumably be less of an immediate need for induction. And seniority-based layoff rules mean that teachers who have pursued new roles as coaches and mentors could find themselves assigned back to classrooms.

ŌĆ£I think that reducing the numbers of support staff in the short run is probably an inevitable tool,ŌĆØ said Liam Goldrick, the director of policy for the New Teacher Center, which supports intensive mentoring programs for teachers. ŌĆ£But if steps are being taken to gut or lower the quality of these programs or eliminate them entirely, thatŌĆÖs where the danger lies.ŌĆØ

Some districts have carefully chosen to preserve their coaching programs.

In Fairfax County, which is struggling to fill a budget hole, the school board planned to cut the coaching program by half. But support from regional superintendents, testimony from Ms. Ritchie and a colleague, and data suggesting that coaching helped narrow achievement gaps led the board to preserve the positions.

In Los Angeles, meanwhile, the school district recently struck an agreement with the teachersŌĆÖ union to pare back the number of positions to be cut to 1,400, from 5,200, in exchange for furlough days.

Decisions about which teaching positions will be preserved will be made by ŌĆ£site-based councilsŌĆØ at individual schools.

Some may choose to keep coaches in place, while others could decide to put all personnel funding into classroom teachers to further lower class sizes, according to Vivian K. Ekchian, the districtŌĆÖs chief human-resources officer. (ŌĆ£Amid Fiscal Crisis, L.A. Gives Site Councils Budget Reins,ŌĆØ July 15, 2009.)

As of three years ago, she added, the district stopped bringing on new teachers except in chronic shortage areas.

ŌĆ£We know just hiring without looking at staffing needs isnŌĆÖt fair to the teachers,ŌĆØ Ms. Ekchian said, ŌĆ£and itŌĆÖs not budgetarily sound for us.ŌĆØ