They checked and double-checked disaster plans to make sure they were ready for chemical attacks by terrorists. Some walked through evacuation drills to make sure students knew what to do in case of an assault.

Principals also reviewed policies for teachers on how to talk with students about a war, and discussed whether to use television as a teaching device when the live coverage could turn bloody at a moment’s notice.

And they rallied their school counselors to ensure they were prepared to help students and staff who might be struggling with emotional strains.

Above all, school leaders worked to keep their campuses running according to routine.

“We’re trying to provide as much of a normal school day as possible,” said Susan K. Cox, a spokeswoman for the 737,000-student Los Angeles Unified School District. “We want to have an environment of calm routine for our students.”

Still, the memories of the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on Sept. 11, 2001, and worries that the war could lead to new terrorist onslaughts had school officials preparing seriously.

“We’ve gone from worrying about students having a common cold to students intentionally being harmed by a devastating virus,” said Bill Montford, the superintendent of the 34,000-student Tallahassee, Fla., school district. “Just a few years ago, that would have been unimaginable.

“It’s taking a toll on our teachers and principals,” he said. “As hard as they try to be positive, it’s still very difficult.”

Just in Case

Many schools spent last week preparing for any traumatic repercussions from the war, which had been seen as a virtual certainty in the days before the first airstrikes on Baghdad on March 19. Schools across the country reviewed their disaster plans and stockpiled water, food, and other supplies that might be needed in case of a chemical, biological, or other barrage.

In Philadelphia, schools have prepared for a possible chemical attack by conducting occasional “shelter in place” drills, in which windows and doors are locked and sealed, and heat and ventilation systems are shut down. Yellow placards are placed in windows indicating a school is in the shelter-in-place mode, said spokeswoman Amy Guerin.

All schools in the 200,000-student district now have shelter-in-place kits, which include student- enrollment lists, school floor plans, emergency phone numbers, duct tape and plastic for sealing windows, first-aid supplies, battery-powered radios, and walkie-talkies. They also keep a day’s supply of food and water.

Schools in the District of Columbia went one step further: Many of them practiced their shelter-in-place drills.

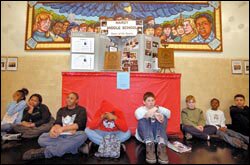

|

Students practice a “shelter in place” drill at Rose L. Hardy Middle School in Washington. |

At Rose L. Hardy Middle School in the Georgetown section of the nation’s capital, solemn-faced teachers and students dutifully followed instructions during their practice drill the day after the bombing started in Baghdad. Individual students were given small tasks to complete— such as turning out the lights—and then all 420 students sat silently in the school’s hallways for three minutes.

While District of Columbia staff members and students have been participating in drills for the past few weeks, the war has heightened the sense of urgency to make sure every school in Washington practices those plans, said Louis J. Erste, the 67,000-student school district’s chief operating officer.

Although Washington is considered a prime target for a possible terrorist attack, Mr. Erste urged all districts to take their emergency plans off the shelf.

“Even if your [emergency] plan is not 100 percent perfect,’' he said, “if you’re 100 percent prepared to implement the plan, you’re going to be better off.”

But the Rising Tide Charter School in Plymouth, Mass., hasn’t been practicing its well-honed disaster plan lately.

Since it opened five years ago, the school has prepared well to whisk its 225 students to safety in case of a radiation leak at the Pilgrim Nuclear Power Plant, just five miles away. The school has a supply of potassium iodide pills, which act as an antidote to radiation poisoning. It also is prepared to implement the detailed evacuation plan prepared by the city.

That may help to account for Jill Crafts’ even-keeled approach to the war. The charter school director has a crisis plan, but the conflict in Iraq and the heightened national terrorism alert—now at code orange, the second-highest level—haven’t sent her into a whirlwind of new preparations.

“Our posture here is certainly to be aware,” Ms. Crafts said. “But we’re trying to take a business-as-usual attitude in the school.”

In New York City, meanwhile, Deputy Schools Chancellor Anthony E. Shorris urged school leaders in a March 18 memo to review their safety plans and make sure all school personnel “are prepared to assume their roles” in case of emergency. Evacuation routes and locations should be known to all, the memo says, and administrators “must remain vigilant” in staying informed of conditions around their schools, which serve a total of 1.1 million students.

Flexible Plans

The Fairfax County, Va., schools have a tiered readiness-and-response plan designed to correspond to each color of the national terrorist alerts, from the low-level green rising all the way up to red. The district has trained staff members in such areas as threat assessment, front-office security, and crisis communication.

|

The poster board lists the duties assigned to Amy Boccardi’s 8th graders at Hardy in the event of an emergency. |

In the event of a code red, the 161,000-student district in the Washington suburbs is prepared to evacuate students or protect them in school buildings, depending on the threat; to increase building security; and to coordinate its crisis response with county agencies.

But even with such a plan in place, the watchword in the district is flexibility.

“We have to respond to what the threat is,” said Paul Regnier, a spokesman for the Fairfax County district. “Until we know the exact nature of a specific threat, we won’t know whether to keep kids in school, or let them out. We can’t take action except to be prepared for anything.”

Sommieh Uddin, the principal of Crescent Academy International, an Islamic school of 275 children in Canton, Mich., said her staff was reviewing its disaster plan, as were staff members at other schools, but with the added awareness that “unstable” people could take out their hostility on Muslim students.

“The people around us have been nothing but friendly and courteous,” she said. “But you have to make sure your students are protected as much as possible from nutty people that would take action at a time like this.”

TV or Not

Educators needed to prepare for any possible threat to their students. But they also faced the pressing question of how to order the school day once war began.

Some teachers made the war the topic of the day, while others decided to avoid discussions of the conflict.

In Joe Rosewell’s classroom at Parkway South High School in Manchester, Mo., the television set is often tuned to 24-hour cable-news programs, which have become essential viewing for students in his current- events course. Late last week, it was a lifeline as he and his class tried to get up-to-the-minute information on the events unfolding in Iraq.

Some schools and districts, however, have effectively banned live news coverage in the classroom.

In Maryland, the 108,000-student Baltimore County district— a suburban system outside the city of Baltimore—instructed teachers not to watch live news of the war on classroom televisions with their students. Many parents had called to complain that children had been upset by the graphic images when they watched the news of the September 2001 terrorism unfold on classroom TVs, said district spokesman Charles Herndon.

“We understand the need of teachers to keep up with what is going on, and [their view that] it’s history in the making, and as such, it’s educational,” he said, “but we have to be careful of the impact on children.”

Officials in the 17,500-student Plymouth-Canton district outside Detroit also turned off the TV sets.

“Coverage has become increasingly graphic, and we do not want to upset students,” Superintendent Jim Ryan wrote in a letter to parents. “These discussions are better held at home.”

In addition to planning for children’s physical safety, schools were doing their best to remain alert to pupils’ emotional states.

At Sims Elementary School in Conyers, Ga., an Atlanta suburb, counselor Karen Griffith organized a support group for relatives of military personnel deployed for duty in or around Iraq. The first meeting, on March 18, drew about 38 attendees from the 14,000-student Rockdale County school district, ranging from children whose mothers or fathers were deployed for the war effort to a grandmother whose daughter had shipped out, she said.

“The children are bubbling over, really wanting to talk about it,” said Ms. Griffith. “They are sad and missing their parents and wanting desperately for people to listen to them.”

Ms. Griffith led the youngest group, the elementary school pupils, in building “memory boxes.”

“There are so many things they wish they could share with the parent who is gone, but when they come home, the kids can’t remember everything,” she said. “So this way, each time something happens that they want to share, they can put an item in the box, to remind them, like a report card or a picture, to talk about when [the parent] comes home.”

Assistant Editor Kathleen Kennedy Manzo contributed to this report.