When California Teachers Association President Barbara Kerr met with Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger last month, she had one pressing question: “What happened to the man we knew last year?”

Education groups believe that the governor reneged on a handshake deal he had made with them when he announced in his State of the State Address in January that, due to the state’s continuing fiscal crisis, he was proposing increases in K-12 spending that were $2 billion short of what they say schools were owed.

Further fueling the ire of the teachers’ unions, he’s charging forward with proposals for introducing merit pay for teachers and overhauling their tenure and pensions systems. The governor, a Republican, also is leading a move to place an initiative on the California ballot in the fall that critics say would weaken the state’s constitutional guarantees for education funding.

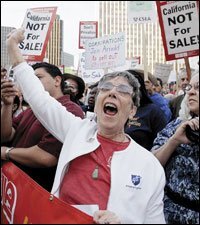

With a once-amicable relationship shattered, both sides are now plotting to raise and spend tens of millions of dollars to press their points. In the meantime, members of the CTA and other education groups have been turning out for spirited protests at Gov. Schwarzenegger’s public appearances and fund-raising events.

“This is a war, and these sides have really reached a point in which they’re in a dogfight,” said Michael W. Kirst, a co-director of Policy Analysis for California Education, an independent research and policy group known as PACE, and an education and business professor at Stanford University. “I have never seen this level of anger and hostility.”

Both sides are facing enormous stakes: The CTA and other education groups are putting huge sums of their money and energy into a fight with an unusually glamorous governor. And Mr. Schwarzenegger, who is already seeing dips in popularity polls, risks further dimming his political star should he come up short.

The CTA, an affiliate of the National Education Association, is considering adding $60 a year to its members’ dues, which now run about $500 annually, to raise about $50 million to continue a media campaign across the state.

Defining ‘Special Interests’

“He has backtracked on his promise to teachers, backtracked on his promise to students, and backtracked on what he told the public during his campaign,” Ms. Kerr said. “He’s sort of become the worst definition of a politician.”

Gov. Schwarzenegger has countered that education groups are among the “special interests” bent on impeding his plans for selfish purposes. The former bodybuilding movie star is campaigning across the state and raising money to persuade voters that change is needed.

Most notably, he’s pressing for the “California Live Within Our Means Act,” an initiative that would give him and future governors power to make across-the-board cuts in the state budget in times of fiscal crisis—an affliction that California can’t seem to cure and that helped lead to the downfall of former Gov. Gray Davis. Mr. Schwarzenegger won the governorship in a dramatic recall election in November 2003 that ousted Mr. Davis, a Democrat.

“We need to deliver big solutions for the big problems we face, including a huge fiscal crisis that will only get worse if we don’t take action right away,” Mr. Schwarzenegger said in a speech this month announcing plans to collect signatures to put some of his plans on the statewide ballot later this year. “It’s time to put the pressure on and have the people send the message that they demand reform.”

In 1988, Californians passed Proposition 98, a constitutional amendment that, in essence, guarantees that public schools will receive at least the same amount of money as the year before, except in extreme fiscal crises.

Last year, after facing a budget deficit of more than $30 billion out of an estimated $80 billion general-fund budget, Gov. Schwarzenegger and the education groups hammered out a deal to “temporarily suspend” Proposition 98 and give schools only a slight increase.

This year, the governor announced a fiscal 2006 budget proposal that would lift funding for education by $2.9 billion, out of a $36 billion state K-12 fund. That would still fall more than $2 billion short of what education groups say Mr. Schwarzenegger had promised.

He also called the legislature into an ongoing special session to consider, among other matters, a plan that would build a system of performance-based pay for teachers and make changes to the teachers’ pension funds. (“Schwarzenegger Takes School Plans to Voters,” March 16, 2005.)

And his supporters are collecting signatures to put the items on a ballot initiative in a special election this November, should the legislature reject them.

GOP leaders defend the governor’s decision to reject the option of raising taxes, saying that would undermine the economy. “We have been fiscally bankrupt for three years or so, and without raising taxes, the governor had to make cuts at various places,” said California Secretary of Education Richard J. Riordan, the governor’s chief education adviser. “I admire his moral backbone for doing what he did.”

But a host of prominent Democrats, including Superintendent of Public Instruction Jack O’Connell, a state senator before he was elected to his current nonpartisan post, are campaigning against the governor’s proposals. “This is the most direct assault I’ve seen in my years of public service,” Mr. O’Connell said at a rally last week. “By decimating the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee for education, California schools would be permanently consigned to the basement in funding.”

Protesters, many of them teachers, have dogged Gov. Schwarzenegger at his recent appearances. In January, at an event in Long Beach, Calif., he responded to a group that interrupted his speech.

Protests Mount

“Pay no attention to those voices over there, by the way,” he said. “Those are the special interests, if you know what I mean, OK? The special interests just don’t like me in Sacramento because I’m always kicking their butt. That’s why they don’t like me.”

That remark has made the CTA more determined. Last week, the teachers’ union joined with the California Nurses Association to unveil another radio ad to combat the “special interest” label: “Teachers and nurses aren’t special interests you need to battle, Gov. Schwarzenegger, they’re at the heart of our communities, working to improve our health care and strengthen our local schools,” the ad says.

A Jan. 27 poll by the Public Policy Institute of California, a nonpartisan research group, showed that education had resurfaced as state residents’ top policy concern, jumping from 15 percent to 22 percent.

At that time, 51 percent of the 2,000 residents surveyed disapproved of the governor’s handling of education issues, while 34 percent approved. The margin of error was 2 percentage points.

Overall, Gov. Schwarzenegger held a 60 percent approval rating, down slightly from 64 percent in the same survey in January of last year.

Some say the governor has underestimated the education groups.

“Every one of the statewide education groups is going to try to bring the maximum amount of resources they can generate to help with this effort, given that basic school funding protections are at stake,” said Kevin Gordon, the president of School Innovations and Advocacy, a Sacramento lobbying firm that represents districts and education groups.

Mr. Riordan, though, is optimistic that the governor and legislators can work together and avoid a costly election on the ballot initiatives. He said that the CTA and other groups are out of touch with what their members want.

“The governor and the vast majority of teachers think there should be accountability, and he wants a system where people will be held accountable,” Mr. Riordan said. “Right now, we have a dysfunctional system, and just throwing money at a dysfunctional system is dooming another generation to failure.”

Meanwhile, the CTA’s Ms. Kerr said the governor did not answer her question at their meeting in February. She hasn’t met with him since.