In 1989, the Springdale School District in northwest Arkansas had 7,691 students, 96.96 percent of whom were white. The remainder of the student body looked like this: 94 Asian and Pacific Islanders, 74 Latino students, 61 Native Americans, and five students who were African-American.

In the last two decades, the districtŌĆÖs population has nearly tripled, with the growth accompanied by an equally dramatic demographic change in the student body. This transformation was due mainly to the economic boom of the 1990s, as immigrants, many of them from Latin America and the Marshall Islands, flocked to available jobs at big businesses in the city and its surrounding areas and industriesŌĆöincluding Wal-Mart, Cargill, and Tyson Foods.

By the 2012-2013 school year, white students accounted for only 40.6 percent of enrollment, and Asian and Pacific Islanders accounted for 11.38 percent, Hispanics, 43.7 percent, or nearly 8,000 studentsŌĆömore than the districtŌĆÖs entire student body in 1989.

Staff writer Denisa R. Superville spoke with Springdale Superintendent Jim D. Rollins, who arrived in the district in 1980 as the director of secondary curriculum and instruction. Listen to the interview:

Below are excerpts from the interview, which has been condensed and edited for space.

What was the districtŌĆÖs initial response to the new influx of immigrants?

Rollins: This district has operated, certainly during the time that IŌĆÖve been [here], with really a guiding philosophy of ŌĆśteach them allŌĆÖŌĆöteach all children to the highest possible levels. We were really trying to develop individual education plans for each child. So, when our immigrant population moved here, we were able to pick up, and to extend that same concept [to them].

Very few of our teachers were bilingual. It was a matter of becoming oriented to the language, familiar with the language, really understanding the culture of our Hispanic families, at that point in time. Today, we have about 1,500 certified teachers, and each of those teachers has had significant training in terms of working with students from different backgrounds, different languages, etc., and about 40 percent of our teachers have gone back to school, have obtained whatŌĆÖs referred to as an esl endorsement from area colleges and universities.

ŌĆśTeach them allŌĆÖ was the driving force in 1980. It continues to be the driving force today.

Can you talk about some of the specific programs that you implemented in the initial years?

Rollins: The first thing we had to do was to reorganize our enrollment process. When children enter our district, we want to know exactly where they were in terms of their readiness to learn. We administered English-language surveys. We found out the number of children who were at entry level, levels 2s, 3s, 4s, 5s, because we understood quickly that children had to be in levels 3 or 4 to really deal with the content of the regular or traditional classes. There was a significant immersion initiative early on. We had to create that division of accountability for our immigrant population, and today that is a significant part of our service area for the district.

Another very significant part of this is we realized early on that there is a normal transition [for immigrant families], and thatŌĆÖs fraught with all kinds of issuesŌĆöjust people trying to get settled, people learning how to interact in that particular community, people learning how to access public services, but unless one really extends themselves and goes the extra mile, I think there can be an enormous gap between home and school.

Our building principals, some eight to 10 years ago, had an effort to address this need. [They worked] with the National [Center for Family Literacy], and we developed, in cooperation at that time with the Toyota Corporation, a family literacy model, which continues today. We brought Hispanic families into the schools to be learners right alongside their children. Those families would come to the schools four days a week, four hours a day, and they would learn right along with their children. In addition to that, there would be adult education classes and family survival skills classes. That program today is kind of a model for the nation, and weŌĆÖve grown from those initial three schools to 13 schools today, and weŌĆÖre continuing to try to lay the foundation for that family literacy initiative in all 30 of our schools.

WeŌĆÖre making progress. WeŌĆÖve got additional work to do, but I am so appreciative of the principals, the teachers who extended themselves, who changed their delivery system so that it can include ELL moms and dads. And when that happens, magical things come alongside: That gap disappears, your ELL families who might have been struggling with that transition through efforts like this now become more and more comfortable. They become enormous advocates for their schools and their teachers and that just boosts the entire educational experience for these children.

What were some of the challenges you faced in the beginning, in developing programs, expanding outreach, and even possibly in getting funding for these programs for students?

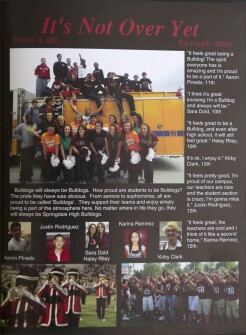

Pages from Springdale High SchoolŌĆÖs 2012 and 1975 yearbooks reflect the Arkansas districtŌĆÖs changing student demographics.

1975:

2012:

Click the image to enlarge.

Rollins: We borrowed from districts around the country. We created programs for newcomers depending on where they were with the language. We really adjusted the delivery of instruction because it could not just be a teacher standing in front of the class delivering a lesson because kids obviously would struggle themselves with their language readiness.

So you had to alter the way you organized time. This idea of immigrant children learning in groups became very evident; so cooperative learning became a major lesson that we learned more and more about.

Since so many of the immigrant children were children of poverty, we continued to emphasize and develop the studies of generational poverty and how that needed to be interfaced with at the school level.

We had to adjust classes, again to accommodate the differing readiness levels. We created sheltered classes, sheltered classes in English and mathŌĆöagain to help with that transition period. But we were very careful to keep our focus based on ongoing assessment data in such a manner that these kids didnŌĆÖt languish in low-level classes.

Your staff is still predominantly white, [but] the number of Hispanics has increased over the years. In addition to [recruiting former students] is there anything else that youŌĆÖre doing to diversify the staff to be more reflective of the student body?

Rollins: It is our goal, I have said publicly that we want to bring forward a staff that reflects the makeup of our student body. ItŌĆÖs an enormous growth area for us, simply because we donŌĆÖt have many candidates applying. If we have good candidates, they are virtually assured of a position here, but itŌĆÖs a long-term growth process. We send teams across the country, to Texas, and Arizona, and California, to try to share the good news. ... .[that] there is work here, there is success orientation here, and that we need you. But weŌĆÖve had more success it seems to me in terms of growing our own than bringing in people new to the area. So growth process, yes, without question.

How many of your students have returned [as teachers], and why is it important to have your graduates return to the district as teachers?

Dr. Rollins: That example is probably as powerful or serves as good a model as anything that we can do because those young people have lived the experience. They felt the supportŌĆöor the lack of it, if that were to be the caseŌĆöand they know firsthand the needs that immigrant children have, and they can begin to build that relationship and share the positives that spring from that.

What advice do you have for other school districts that are only now beginning to deal with this change?

Rollins: These are just children. They deserve our best effort. We may well have to redefine ourselves in order to serve those needs. The willingness to stretch and grow and build capacity within your team to serve children from all backgrounds is an ongoing issue. And if the commitment exists to teach all children, our public schools will find a way to do that. I would just say that the wins here far outweigh the kind of challenges that you have.

We just had a young lady graduated this past year, which warmed my heart about as much as one could imagine. Here is a young lady who came to our district in poverty, virtually non-English speaking, and as she graduated from our Springdale High School she earned a full scholarship to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, one of the finest engineering schools in the nation. And thatŌĆÖs just one success story. I could repeat it over and over and over again. But when you see children connect with the learning, begin to realize their potential and promise, and you see families come together, united in an effort to support the teachers and the school, it doesnŌĆÖt get much better than that.