In a large black-and-white photograph hanging in Jane StassenŌĆÖs office, 1930s-era construction workers perch on a thin steel beam some 70 stories above New York City, precarious but undaunted as they read newspapers and eat lunch on a break.

ItŌĆÖs no accident that Ms. Stassen, the director of curriculum and instruction for the 3,200-student South St. Paul school district, keeps this image on view above her desk. She sees a parallel to the cash-poor districtŌĆÖs plan to become what would apparently be the first public school system in the nation to offer the demanding International Baccalaureate program to all its students by next fall.

ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖre going confidently out on a limb,ŌĆØ Ms. Stassen explained. As to why a small community best known for its long-gone meat-packing plants would choose to put itself in the vanguard of education reform, district officials say the driving force was pretty cut and dried: the need to prepare students to compete for 21st-century jobs.

ŌĆ£What we want is for all our kids to pursue postsecondary [education],ŌĆØ Ms. Stassen said. ŌĆ£In order to prepare them for that, we need to offer them rigorous, challenging academic experiences, and thatŌĆÖs basically what [IB] is all about.ŌĆØ

The perception that the Geneva, Switzerland-based offer just what American students need in todayŌĆÖs more globally competitive environment seems to be catching on.

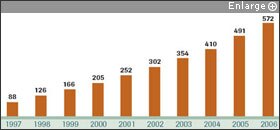

After decades of obscurity and slow expansion, the pace of growth in IBŌĆöincluding courses of study for the primary and middle school years as well as the better-known high-school-level programsŌĆöhas quickened considerably.

Favorable word of mouth among educatorsŌĆöalong with an endorsement from President Bush and glowing accounts in national magazinesŌĆöhas helped catapult IB into U.S. classrooms. More than 225 American schools so far this year have started offering at least one IB program, bringing the U.S. total to 800.

The process of becoming IB-authorized and offering IB classes can be expensive and time-consuming, and the research base on IBŌĆÖs efficacy in the United States at this point is thin. Still, more and more schools seem to be arriving at the conclusion of Kathleen Johnson, South St. Paul Junior High SchoolŌĆÖs head of school: ŌĆ£This is probably the best K-12 education you can get.ŌĆØ

Different observers have different theories about whatŌĆÖs behind IBŌĆÖS faster growth in recent years, given that the program does not actively advertise.

Jeffrey R. Beard, IBŌĆÖs director general, says the International Baccalaureate OrganizationŌĆÖs goalŌĆöŌĆ£to prepare students to assume a meaningful role in todayŌĆÖs global societyŌĆØŌĆömeshes well with AmericansŌĆÖ heightened awareness that they must compete for jobs with people on other continents, and that they need a world-class education to succeed.

For years, there has been only a sparse International Baccalaureate presence in the United States, but the number of U.S. schools offering at least one IB program has recently shot up.

NOTE: Figure for 2007 is as of this month.

SOURCE: Courtesy of International Baccalaureate Organization

Mostly eschewing multiple-choice tests in favor of research papers and oral presentations, IB aims to teach critical-thinking skills, partly by training students to examine the bases of truth and bias.

ŌĆ£These are skills that typical adults donŌĆÖt achieve until their 30s or 40s,ŌĆØ Mr. Beard said. ŌĆ£Parents tell us, ŌĆśI canŌĆÖt believe my kid is thinking this way.ŌĆÖ ŌĆØ

IB offers programs for all three main segments of K-12 educationŌĆöprimary school, middle school, and high school. The latter, called the Diploma Program, is the most common of the three in the United States.

Offerings vary from school to school, but each IB school must offer at least one course in each of IBŌĆÖs six content areas, and fulfill uniform curriculum and course guidelines.

ŌĆó About 90 percent of schools in the United States that offer at least one International Baccalaureate program are public.

ŌĆó About 30 percent of IBŌĆÖs U.S. schools receive federal Title I anti-poverty money.

ŌĆó About $10,000 in application fees is required to have a school considered for IB authorization, not including $1,000-per-person IB professional-development courses and other expenses.

Students enrolled in the two-year IB Diploma Program must take a sequence of subject classes, plus a Theory of Knowledge class, and write a 4,000-word research paper on an approved subject of their choice. Diploma candidates must also participate in 150 hours of what IB calls Creativity, Action, and Service, which includes extracurricular arts, sports, and community service.

Alternatively, although all IB schools must offer the full Diploma Program, students can opt to take individual IB classes.

The Diploma Program culminates in studentsŌĆÖ senior year with three to five weeks of oral and written assessments, which count for three-quarters of their final grades.

To earn an IB diploma, students must score at least 24 of 42 possible points on exams across each of IBŌĆÖs six content groups: one first language; one acquired language, in which students must be fluent; individuals and societies, including business, philosophy, and history; experimental sciences, including physics and design technology; the arts; and mathematics and computer sciences.

Students can receive up to three additional points for their work in the Theory of Knowledge class and for their Creativity, Action, and Service participation.

South St. Paul is smallŌĆöjust over 20,000 peopleŌĆöand it takes less than a minute to drive from the district office to South St. Paul Senior High School, a red-brick structure that graduated its hundredth class last year.

International Baccalaureate began operating in 1968 largely as a way for the children of European diplomats, business executives, and other professionals to keep up with their college-preparatory studies during time spent abroad.

The first IB graduates received their diplomas in 1970ŌĆöthe year Peru, Ill., publisher M. Blouke Carus happened to see a tiny story about IB in the International Herald Tribune newspaper. The program got started in the United States a year later.

ŌĆ£Blouke was probably the major reason [IB] came to the United States,ŌĆØ said IB Director General Jeffrey R. Beard. ŌĆ£HeŌĆÖs always been concerned about international competitiveness.ŌĆØ

Mr. Carus is American, but he studied for a semester in 1939 at a school in Germany when he was a boy, and was struck by how much more challenging the academics were there.

After getting his bachelorŌĆÖs degree at the California Institute of Technology, in Pasadena, Calif., and studying further abroad, Mr. Carus went on to develop and publish, among other education titles, the Open Court Reading series now published by SRA/McGraw-Hill, a division of the New York Citybased McGraw-Hill Cos. Inc. He worked to persuade IB officials in Geneva to branch out to North America, and the first U.S. IB schoolŌĆöthe United Nations International School in New York CityŌĆö was authorized in 1971.

South St. Paul, Minn., began offering IB at its high school in 1986, after David Metzen, then the districtŌĆÖs superintendent, happened to see an IB class in action on a bus trip to inner-city Milwaukee.

ŌĆ£IŌĆÖd never seen kids and teachers so turned on,ŌĆØ he said. ŌĆ£I said, ŌĆśWhat is this?ŌĆÖ and they said, ŌĆśInternational Baccalaureate.ŌĆÖ I said, ŌĆśInternational what?ŌĆÖ ŌĆØ

Mr. Metzen, now a regent of the University of Minnesota, managed to persuade the school board to give IB a try, though, he added, ŌĆ£IŌĆÖm the first one to say I didnŌĆÖt know if it would be successful.ŌĆØ

ŌĆöScott J. Cech

Inside on a recent school day, the hallways were swarming with students, faculty, and administrators wearing maroon-and-white ŌĆ£PackersŌĆØ sweatshirts and jacketsŌĆöa show of school spirit for the boysŌĆÖ soccer team, which had a big game that afternoon.

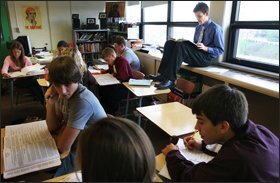

One of those soccer players, 18-year-old Keith Lowery, was sitting at his desk in teacher and IB coordinator Angie RyterŌĆÖs IB Biology 2 class, dividing his attention between the dayŌĆÖs lesson on evidence for evolution and integral problems in his Calculus 2 textbook.

When he transferred to South St. PaulŌĆÖs public schools from a local private school in 7th grade, he found the academics ŌĆ£way too easy,ŌĆØ and when he got the chance to take IB courses, he jumped.

ŌĆ£I like being challenged,ŌĆØ said the senior, who plays goalie and said heŌĆÖd like to study engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology, in Atlanta, or maybe at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in Cambridge, Mass.

Nevin Shenouda, a 17-year-old girl of Egyptian heritage who sat up front, said she was also drawn to the program for the challenge, and compared it favorably with Advanced Placement classes, which friends outside the district have taken.

ŌĆ£IB makes you think,ŌĆØ she said. ŌĆ£APŌĆÖs just a lot of memorizing and then writing it down.ŌĆØ

Then thereŌĆÖs the college-tuition factor. Ms. Shenouda has already been accepted by the University of Minnesota, which sheŌĆÖs weighing attending, in part because if she earns a score of at least 30 out of 45 possible points on her IB final exams, sheŌĆÖll be eligible to skip up to a year of classes there. She said the university gave her sister, who graduated in 2006, $1,000 in scholarship money just for having taken IB classes.

Other universities offer even more. At Oregon State University in Corvallis, Ore., an IB final-exam score of 30 or higher confers automatic admission, a yearŌĆÖs worth of creditŌĆöworth about $6,000 for in-state students and about $18,000 for students from out of stateŌĆöand a minimum of $2,000 in scholarship money, renewable annually so long as the student maintains a 3.0 grade point average.

ŌĆ£Does it help with recruitment? Yes,ŌĆØ said Michele Sandlin, the universityŌĆÖs director of admissions, but she added that only about five incoming freshmen per year manage to score a 30 or above. Ms. Sandlin said Oregon State offered the credit in part because IB-graduate freshmen were testing out of so many classes.

Because IB has only lately popped up on many educatorsŌĆÖ radar screens, there have been no national studies of its relative effectiveness in educating students or preparing them for college.

But Ms. Sandlin said sheŌĆÖs impressed with the quality of IB-educated applicants she sees.

ŌĆ£The IB students that we get are very prepared for college,ŌĆØ she said.

While IB has grown markedly in the United States, itŌĆÖs still dwarfed by Advanced Placement, the Goliath of college-prep programs.

More than 15,500 U.S. public and private schools offered AP exams last year, a number thatŌĆÖs roughly equivalent to the number of high schools offering an AP class, according to the New York City-based College Board, which sponsors the AP program.

While IB and AP are sometimes mentioned in the same breath, said Carolyn M. Callahan, the chairwoman of the department of leadership, foundations, and policy at the University of VirginiaŌĆÖs education school, in Charlottesville,Va., both programs are strong, but not really comparable.

ŌĆ£I wouldnŌĆÖt say [IB] is AP on steroids so much as a different kind of program across the board,ŌĆØ she said.

Still, Ms. Callahan said IBŌĆÖs reputation has grown as the luster of AP courses has dimmed a bit. Amid complaints that AP courses have become less challenging as more students enroll in them, as well as a series of AP exam-scoring gaffes last year, ŌĆ£Advanced Placement came under considerable criticism,ŌĆØ she noted.

Ms. Callahan, who is one of a very few impartial researchers in the United States to have extensively studied IB, said the College Board has actually ŌĆ£tried to mimic IB,ŌĆØ by establishing the Advanced Placement International Diploma.

ŌĆ£I think IB has taken on a mantle of prestige,ŌĆØ she said.

Spokesmen for the College Board did not respond to requests for comment on that view or to a request to comment generally on IB.

Some schools have dropped IB, though, because of community preference for AP.

W.T.Woodson High School, a highly regarded public school in Fairfax,Va., decided eight years ago to discontinue its IB offerings after parents complained that the program allowed less flexibility for studentsŌĆÖ extracurricular activities than AP.

ŌĆ£Ultimately, I believe the consensus was that Woodson had an AP program already in place that was very successful,ŌĆØ said Robert Elliott, whoŌĆÖs retiring as the principal of the school next month. ŌĆ£There are aspects of the IB program that are ŌĆ” uniquely great,ŌĆØ he added. ŌĆ£I think many people in the community wouldŌĆÖve liked to offer both programs, but thatŌĆÖs hard to do, especially in these financially tight times.ŌĆØ

Ms. Callahan believes that the cost of IB, as itŌĆÖs currently set up, will prevent it from ever growing as widespread as AP.

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs an extremely expensive program,ŌĆØ she said of IB. ŌĆ£Sadly, many communities are not willing to invest.ŌĆØ

It costs about $10,000 in application fees to get a school considered for IB authorization, and that doesnŌĆÖt include the travel and other costs of sending the schoolŌĆÖs teachers and coordinators to specialized three-day professional-development courses, which cost $1,000 per person. Even after being authorized, IB high schools must pay $8,850 a year in fees. Middle and primary schools must each pay $5,220 annually, though schools with more than one IB program get a 10 percent overall fee discount.

Schools must also pay additional fees per student and per subject, and those costs donŌĆÖt cover mailing expensesŌĆöall exams are physically mailed to graders, many of whom are overseas.

To hear South St. PaulŌĆÖs Ms. Stassen tell it, money wasŌĆöand continues to beŌĆöher districtŌĆÖs biggest problem in implementing IB.

ŌĆ£The local pushback has been, ŌĆśCan we really afford this?ŌĆÖ ŌĆØ she said.

South St. Paul Superintendent Patty Heminover said the district has spent about $626,730, supplemented with money from the nonprofit South St. Paul Educational Foundation, on IB just since the start of this school year. ThatŌĆÖs not small change in a district that shares its headquarters building with a drugstore. South St. Paul schools spent a total of $30 million for all of the 2006 fiscal year.

ŌĆ£What we had to do was take a look at our resources and reallocate,ŌĆØ Ms. Heminover said. Since 1997, the district has halved the percentage of budget it spends on administration, letting its communications and grant-writer positions go unfilled and tightening up its already lean finances elsewhere.

Financially, ŌĆ£itŌĆÖs a difficult thing to be a small district,ŌĆØ Ms. Stassen said. But she added: ŌĆ£EveryoneŌĆÖs just one step from the classroom, and thatŌĆÖs what makes a differenceŌĆö what happens in the classroom.ŌĆØ

Although the IB organization expects to continue to grow aggressively in the United States, IB leaders intend to expand the programs with a specific type of student and school in mind.

While ŌĆ£we get the label of being elitist,ŌĆØ Mr. Beard said, about 30 percent of IB schools in the United States receive federal Title I anti-poverty money. The organization would like to dramatically increase the overall proportion of IB students who are eligible for free and reduced-price lunches.

ŌĆ£WeŌĆÖre focusing on schools with Title I,ŌĆØ Mr. Beard said.

Some high schools require prospective IB students to pass an entrance test before allowing them into the Diploma Program, he said, which tends to screen out those with lower incomes: ŌĆ£What weŌĆÖre telling [high schools] is, let them all in.ŌĆØ

Ms. Ryter, the biology teacher, noted that, if all goes as planned and the districtŌĆÖs elementary and junior high schools are authorized by the IB central office to offer full IB programs starting next fall, much of the intimidation that keeps more students from taking International Baccalaureate in high school will likely disappear.

Because, unlike in high school, all students at primary- years IB schools must take IB, ŌĆ£they wonŌĆÖt see it as, ŌĆśOh, thatŌĆÖs only for the smart kids,ŌĆÖ ŌĆØ Ms. Ryter said.

Indeed, when asked to compare IB classesŌĆÖ difficulty with that of non-IB classes, a group of 11-year-old students from South St. PaulŌĆÖs elementary-grades Kaposia Education Center just gave quizzical looks.

Because theyŌĆÖve been in classes already ramping up their academics as part of KaposiaŌĆÖs IB candidacy, they donŌĆÖt know anything different. To them, the academically demanding, internationally oriented curriculum is just the way school is.