Corrected: This story on bid specifications for a new five-year What Works Clearinghouse contract should have said that the current contract is worth $23.4 million. The story also should have made clear that while the clearinghouse gives its highest ratings to randomized control studies, it also considers other kinds of studies that compare treatment and control groups.

Includes updates and/or revisions.

As the federal What Works Clearinghouse rolls out long-awaited ratings on the effectiveness of math programs for the elementary grades, one trend is becoming clear: Most major commercial textbooks canŌĆÖt yet muster the proof that they are any better than their competitors at improving student achievement.

Of four reviews published by the online clearinghouse since September, only one elementary school math program has received even a qualified nod from evaluators for its research record.

Yet while publishers and textbook evaluators are concerned about the message those lukewarm effectiveness ratings may send, they also say the ratings may have more to do with the clearinghouseŌĆÖs strict reporting system than with the programs themselves.

Read the related story,

The What Works site says a handful of rigorously conducted experiments show that Everyday Mathematics,published by Wright Group/McGraw-Hill of DeSoto, Texas, has ŌĆ£potentially positive effectsŌĆØ on achievement compared with more traditional math programs.

The other programsŌĆöHoughton Mifflin Mathematics, Saxon Elementary School Math,and Scott Foresman-Addison Wesley Elementary MathematicsŌĆöwere found in What Works reviews to have ŌĆ£no discernible effectsŌĆØ on learning.

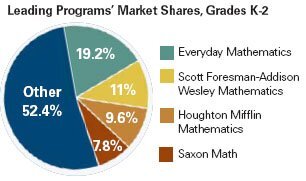

Together, the four programs represent about half the U.S. market for elementary school math textbooks, according to a 2005 survey by Robert M. Resnick, the founder and president of Education Market Research, of Rockaway Park, N.Y.

The What Works project favors randomized-control trialsŌĆöexperiments in which a program or practice is randomly assigned to either a treatment or a control groupŌĆöand ignores or discounts most other kinds of studies. (ŌĆ£ŌĆśOne StopŌĆÖ Research Shop Seen as Slow to Yield Views That Educators Can Use,ŌĆØ Sept. 27, 2006.)

ThatŌĆÖs a problem for publishers, because the comparison groups in their cases tend to consist of schools or classrooms using other popular textbooks.

Math Marketing

SOURCE: Education Market Research

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs very difficult to find significant differences in a one-year study when youŌĆÖre looking at two programs teaching essentially the same content,ŌĆØ said Marcy L. Baughman, the director of academic research for Pearson Education. The Boston-based company publishes the Scott Foresman-Addison Wesley Elementary series, which in December became the latest math-textbook program to be reviewed by U.S. Department of Education-sponsored clearinghouse.

Rebecca S. Herman, the clearinghouseŌĆÖs project director, said such criticisms miss the point. The clearinghouse, which is funded by the departmentŌĆÖs Institute of Education Sciences and housed at the American Institutes for Research, a nonprofit organization based in Washington, is designed to identify the most-effective educational programs and strategies, she noted.

ŌĆ£The point is: Does one work better? Is one really a star?,ŌĆØ said Ms. Herman, the project director for the clearinghouse. ŌĆ£In math, thereŌĆÖs never going to be a situation where students are not getting a math textbook or some sort of math curriculum.ŌĆØ

Misleading Impressions

Publishers and some scholars complain, though, that spare judgments such as ŌĆ£no discernible effectŌĆØ or ŌĆ£potentially positive effectsŌĆØ give the wrong impression.

ŌĆ£If a layperson reads the ratings, he or she is going to think a kid will not improve with this program,ŌĆØ said Mariam Azin, the president of Planning Research and Evaluation Services Associates, an independent group in Jackson Hole, Wyo., that has evaluated several commercial textbook programs. ŌĆ£Well, thatŌĆÖs not true.ŌĆØ

An experiment could turn up no effects if both the textbook under study and the program with which it is being compared are equally goodŌĆöor equally badŌĆöat improving student learning.

Ms. Herman said clearinghouse officials are aware of such concerns, which publishers have been voicing since the ratings system was in the planning stages. In response, she said, federal reviewers have moved some information about the composition of the comparison groups from a technical appendix to the body of the main report.

Still, the clearinghouse should go further, argued Bill Wilkinson, the vice president for research for Harcourt Achieve, the Austin, Texas-based company that publishes the Saxonmath program. He said the What Works site should also put learning-growth data from studies that are not randomized into its main reports to give educators and policymakers more information.

ŌĆ£When youŌĆÖve got so many math programs showing ŌĆśno discernible effects,ŌĆÖ it really makes it hard for the education community to make judgments,ŌĆØ Mr. Wilkinson said, ŌĆ£and, really, the clearinghouse is there for the education community to make judgments.ŌĆØ

Practical Impact

WhatŌĆÖs not yet clear, though, is whether the ratings will carry any weight with the people charged with selecting instructional materials for schools. Texas and CaliforniaŌĆötwo of the three largest states that adopt textbooks at the state levelŌĆöare scheduled to approve new elementary mathematics series this year.

Adding It Up

SOURCE: Education Market Research

The curriculum directors in those states said that the official state criteria for their upcoming adoptions require publishers to ensure that their programs are research-based. Yet they do not require publishers to submit proof that their products work, although that could change in Texas, where lawmakers this spring plan to rewrite the stateŌĆÖs textbook-adoption policies.

Some educators at the district level, for their part, have been demanding that kind of evidence for a few years, in part because of requirements under the No Child Left Behind Act that programs be research based, according to publishers. Mr. Wilkinson of Harcourt said he was even asked recently to provide research showing that students learn more than they otherwise would when they use the flashcards his company produces.

ŌĆ£If thereŌĆÖs a place where they take an objective view of the research, thatŌĆÖs something I would certainly be interested in,ŌĆØ said Lianne B. Jackson, the textbook and standards program coordinator for NevadaŌĆÖs 65,000-student Washoe County school district, which expects to adopt new elementary math texts over the next few years.

But the bottom line for most districts and states is ensuring that the instructional programs they choose adhere to local and state standards on what to teach and when to teach it.

ŌĆ£If you werenŌĆÖt significantly outperforming your competitor,ŌĆØ Ms. Baughman said, ŌĆ£I donŌĆÖt know that it would keep a state or district from adopting you.ŌĆØ

The What Works Clearinghouse is part of a movement at the federal level to spur demand for rigorous research attesting to the effectiveness of educational programs.

The No Child Left Behind Act, for instance, requires that schools receiving funds under the law rely on ŌĆ£scientifically based evidenceŌĆØ in choosing a wide variety of educational programs, products, and practices.

Textbook publishers, in turn, have responded by commissioning randomized trials of their products. While the growth in company-sponsored studies has raised some eyebrows, experts by and large see the mounting piles of evidence as a positive development. (ŌĆ£Houghton MifflinŌĆÖs Sale to Software Maker Reflects Trend,ŌĆØ Dec. 6, 2006.)

ŌĆ£Before, it was definitely more loosey-goosey,ŌĆØ said Ms. Azin of Planning Research and Evaluation Services Associates. But she believes the clearinghouse should expand the range of research that qualifies as evidenceŌĆöa change that clearinghouse operators say they are not likely to favor.

ŌĆ£ItŌĆÖs also dangerous to go to a more formulaic approach, which might be extreme,ŌĆØ Ms. Azin said.