The adults who work in school buildings are overwhelmed and stressed out. And the effects are trickling down to their students, who are contending with a mental health crisis of their own.

Teachers say the past few years in the classroom have been grueling. And even though there are signs of improvement, surveys still indicate that educators generally are not doing well. For instance, the RAND Corp. has found that teachers are stressed at work more often than other working adults. They’re more likely to experience burnout and report a lack of resilience, meaning they bounce back less quickly after stressful or otherwise hard times.

This is a major problem for school districts. Research shows that when teachers are stressed, the quality of their instruction, classroom management, and relationships with students all suffer. Students tend to be more stressed when their teachers are, which in turn hurts their academic performance and classroom engagement. And teachers who are stressed and burned out are more likely to want to leave the profession, adding to districts’ difficulty filling key positions.

But there are things districts can do to help their teachers. In a January EdWeek Research Center survey, teachers themselves named a few: recognizing good work, providing access to counseling, and lightening their workload where possible.

∞ƒ√≈≈Ðπ∑¬€Ã≥ found three examples of initiatives happening in schools across the country that address some of these suggestions and show signs of protecting teachers‚Äô well-being.

District-provided mental health care for staff

Even as districts have worked to bolster mental health services for students, their mental health programming for staff is sparse, past surveys show. The Phoenix Union high school district is working to change that.

The 28,000-student district in Arizona’s capital is in its third year with two full-time licensed counselors whose sole focus is the district’s employees. The district started its employee wellness program with a focus on staffers’ physical wellness, but after the pandemic started, employees’ mental health needs became clear to administrators.

“They’ve got the students taken care of with supportive services, but the only thing they had for adults was your [employee assistance program],” said Erika Collins-Frazier, one of the district’s counselors. “Sometimes EAPs don’t necessarily work in the way we want them to.”

Now, anybody who works for the district—administrators, teachers, and support staff—can meet with a counselor, free of charge and by appointment, for mental health support. The counselors don’t have the capacity to meet with someone regularly and provide ongoing therapy, but they can provide one-off support and connect employees to long-term help.

On one September morning, for example, Collins-Frazier met with two employees. One wanted to talk about how she could better manage her job-related stress. She didn’t want to see a therapist; she just wanted a one-and-done session to learn some practical strategies. Collins-Frazier spoke with her for 45 minutes, suggesting breathing techniques, ways to prioritize her tasks, and tips to reframe some of her major stressors.

“After we were done, she said, ‘I feel so much better, thank you,’” Collins-Frazier recalled.

In the next meeting, the employee was dealing with a personal issue. She needed a therapist whom she could meet with regularly, so Collins-Frazier asked her some questions, then did the legwork to find some therapist options within the district’s insurance network who might be a good fit. (Employees do not have a copay for mental health therapy.)

The conversations are all confidential. “We’ll sneak on your campus, no one will see us—we’ll go into your classrooms to have the conversation,” Collins-Frazier said. Employees can also opt to meet in the district’s central office, off campus at a coffee shop, or virtually.

The counselors also provide what’s known as “process groups” when something traumatic happens in the school community. For example, when a student brought a gun onto one of the district’s campuses, the counselors went to the school and facilitated a voluntary group discussion to help staff process the incident. Those who needed additional support met one on one with a counselor afterward.

At first, some employees were hesitant to seek mental health support at work, said Deana Williams, Phoenix Union’s talent director who oversees the wellness program. But that hesitation is starting to fade over time, she said, and administrators have communicated to their staff that it’s OK to take time for themselves and get help.

Last school year, the counselors had 656 sessions with 301 staffers. This year so far, they’ve had more than 100 sessions with about 70 staffers. (There are about 3,300 staff members in total.)

The two counselors are so busy that the district is trying to hire a third. But that position has been hard to fill, Williams said, given a shortage of mental health professionals that districts across the country have encountered when trying to add to their mental health offerings.

“It’s hard to pay someone what they would earn in the private sector,” she said. “We’re paying therapists a teacher’s salary.”

The district is starting to compile data—on staff absences and requests for leaves of absence, as well as from exit interviews—to understand the counselors’ impact. Ultimately, Williams said, Phoenix Union is hoping the counselors prove helpful with teacher retention.

“These educators, they’re here all day, every day, really trying with everyone’s children,” Collins-Frazier said. “We want them to be in their best mental space—we need them to be in their best mental space. They’re with our kids.”

An app that highlights the good work in schools

More than half of teachers say that something simple—more acknowledgment of their efforts and good work—would support their mental well-being, the EdWeek Research Center survey found. It’s low-hanging fruit that Claire Smith is tackling .

“It really started because I was an insanely burnt-out teacher,” she said.

Smith had been teaching 7th grade math outside of New Orleans during the height of the pandemic. By the time full-time, in-person instruction resumed in the 2020-21 school year, morale throughout the building was lower than it had ever been. Educators were constantly venting about their challenges, which bred more negativity.

“I was feeling like I needed some boost,” Smith said.

She called her best friend, Krissy Taft, a software developer, and through tears, discussed the seeds of an idea: What if they built a platform that allowed people at a school to give shoutouts to others for their hard work? What if the platform emphasized the good in school, instead of the bad?

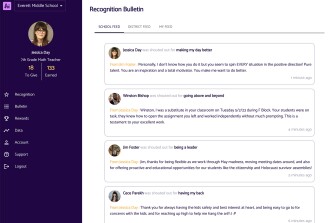

With Hilight, school employees can publicly share compliments about their colleagues. As the shoutouts accumulate, employees on the receiving end can redeem points for rewards. Schools can choose which rewards are up for grabs, including food delivery gift cards, school merchandise, doughnuts for the teachers’ lounge, or having the principal cover a class for a period.

Hilight started in Smith’s own classroom—originally as KidKred, with a focus on student compliments—and then expanded to employees throughout her school. After the 2020-21 school year, Smith had quit teaching to pursue the venture full time. (Taft left her own job to work on Hilight full time as well.)

About 25 schools and districts—both private and public—now pay for their staff to have access to the app. Smith said she expects a few more to sign on by the end of the month. The cost varies based on the school’s size and the package it chooses, but it starts at $3,000 a year per school. (Districts can get a discount for having multiple school subscriptions.)

Immaculate Conception School, a Catholic school near New Orleans, was among those that adopted the app this school year. Brittany Cortez, a 3rd grade teacher, said staff had been in “survival mode” ever since the pandemic’s start.

The teachers’ lounge can be a place where negativity multiplies, as teachers share a laundry list of complaints about their day and others chime in, Cortez said.

“You’re spiraling into everything that went on that day, whereas [with this app], we’re just pointing out the positive, beautiful things that each other are doing,” she said.

The compliments don’t have to be major, Cortez said. Little things, like being called “the rock star of carpool,” can make educators feel validated, she said: “It’s confirmation that you are being seen for the things that you’re doing.”

That’s important, Smith said, because many schools are siloed, and educators feel as if no one notices their hard work: “You’re pouring your heart out, and it feels like you’re making mistakes constantly.”

But, she said, receiving a public compliment can feel validating and reinforce educators’ sense of purpose—both important components of well-being.

PD that blends content knowledge and attention to well-being

In 2022, with some federal COVID-19 relief money in hand, the Arizona Science Teachers Association decided to add a new component to its annual summer institute: training on avoiding burnout and protecting one’s well-being.

The central theme of last year’s institute, packed with content about more effective science teaching, was cause and effect, which lent itself nicely to resilience training, said Alison Smith, a teacher-turned-resilience coach who is leading this work for ASTA. The association included the resilience training again during its institute this past summer.

“These are passionate teachers, and it takes a toll on their well-being,” she said. “There is an effect to outstanding teaching, and oftentimes that trade-off is on their well-being.”

Between content sessions throughout the institute’s four days, teachers discussed the behaviors, systemic challenges, and ways of thinking that are leading them to burn out, and then what could boost their resilience.

Then, they set goals to become more resilient teachers, such as not working on the weekends, making a point to eat lunch every day, or learning to cope with a toxic administrator. Eventually, their resilience goals went even deeper, such as learning to make informed decisions about what can be taken off their plates or changing their mindset of what makes a “good teacher.”

After the institute, teachers sign up for small-group coaching throughout the school year. The groups meet virtually with Smith once a month, and she checks in on members’ progress and facilitates reflection so they can design their own solutions.

For example, a teacher might say they’re swamped with grading. Smith might ask, What’s the purpose of grading? How do you think about feedback, and where is that most needed?

“I’m not an instructional coach, I’m just asking them those questions, and they’re responding with what they’ve learned from their training,” she said.

The questions prompt teachers to think, “You know what, of all these assignments, actually this one or two are the ones that I really need to give the good, juicy feedback on. So let me prioritize my time there instead of trying to grade everything, and then ending up just giving everyone surface-level grades and no feedback,” Smith said.

Sara Young, a high school chemistry and engineering teacher in Phoenix, attended the ASTA summer institute and participated in the resilience training both last year and this year. This year, her main goal is to clarify her classroom procedures so she doesn’t feel frantic during the school day. She wants students to have clarity about what needs to happen every day, and to keep things organized.

Smith’s questioning has encouraged her to reevaluate her work processes, Young said. “She doesn’t give suggestions, she asks questions to make you come up with solutions that work for you.”

Young has also benefited from hearing from teachers in her group about their own challenges and solutions, she said.

One twist: Teachers who signed up for the ASTA summer institute in 2022 had no idea it would include resilience training. (This year, the wellness component was advertised.) It was a pleasant surprise, Young said.

“It was empowering and comforting to have someone realize that, yeah, this is a hard job. All of my SEL training has been how to help students,” she said. “It was really interesting and different to think about, oh yeah, I guess I should take care of myself.”

Fifty-five of the 65 teachers who participated in the 2022 institute signed up for a full year of coaching, Smith said. Fifty-eight teachers from this year’s training did.

The ASTA hopes to continue the resilience coaching, although the group will have to find an alternative funding source as the federal pandemic relief money is set to expire next fall.

“There are some educators who are absolutely still in the classrooms because they’ve gotten this support,” said DaNel Hogan, the science content director for the ASTA symposium. “People really do need lessons and ideas in how to set up better boundaries or how to have this better work-life balance. Without concrete strategies, teachers flounder.”

Data analysis for this article was provided by the EdWeek Research Center. Learn more about the center’s work.