(This is final post in a two-part series. You can see Part One here.)

The new question-of-the-week is:

Do you use rubrics? Why or why not? If you do, how do you use them most effectively? If you don’t, what do you use, instead?

In Part One, Kathy Dyer, Allyson Caudill, John Cox and Ashley Blackley, and Lisa Sibaja shared their recommendations.

Today, Chris Gareis, Peter Liljedahl, and Julia Stearns Cloat “wrap up” this series with their responses.

Rubrics & Soccer

Christopher R. Gareis, Ed.D., is a professor of education at William & Mary. A former English teacher, soccer coach, and principal, he is the co-author of the books Teacher-Made Assessments: How to Connect Curriculum, Instruction, and Student Learning (2015) and Assessing Deeper Learning (2019):

In college days, I was an English major and a four-year varsity soccer player—two loves of my life. It’s not surprising then that I started my post-college adult life as a high school English teacher and varsity soccer coach.

The academic discipline of English and the sport of soccer have more in common than one might initially imagine, and I realized one of the most profound similarities very early in my career. English and soccer are both about performance: writing, reading, speaking, listening, researching, analyzing, interpreting, persuading; dribbling, passing, signaling, repositioning, tackling, diving, heading, shooting. The indicator of learning is what the student or the player is able to do.

If you’re going to gauge performance in the classroom (or on the pitch), you need a rubric. The reasons are clear. Rubrics (a) clarify criteria for students; (b) improve validity, reliability, and efficiency in grading; (c) provide a framework for analyzing student learning so that you can make better instructional decisions; and (d) can be used to provide formative feedback that students can use to move their own learning forward.

But there’s another reason why I use rubrics. The very process of creating a rubric helps me as an educator understand the targeted “performance” better. The better I understand it, the better I can assess it. Also, though, the better I understand it, the better I can teach it.

Understanding the targeted performance of a subject or sport that you love is one thing, but understanding a target performance can be far more challenging when you teach at a new grade level or teach different subject areas (some of which, if we’re honest, might not be your first love). I learned this as my career progressed over the years, taking me from high school in one city to middle school in another town; from English to science and math; and eventually from teaching and coaching to leading and coaching (think, instructional coaching) as an assistant principal and principal.

These new roles pressed me to unpack and deeply understand the new kinds of target performances that I was responsible for fostering in my students and later in my colleagues. The very process of creating rubrics to gauge performance deepened my expertise. The deeper my expertise, the more effective (and confident) I became as a teacher and as an instructional leader. That’s a goal worth shooting for. (Pun intended, naturally.)

Math Rubrics

Peter Liljedahl is a professor of mathematics education at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, Canada. He has authored or co-authored numerous books, book chapters, and journal articles as well as won many awards for math education and excellence. His most recent book is :

I’ve spent some time researching how four-column rubrics affected students learning behavior in the classroom. What I found was that, irrespective of how much time and energy teachers spent in using these types of rubrics as medium for providing students with feedback, 75 percent of students spent less than 10 seconds looking at it. The feedback was being delivered, but for the majority of students, it just was not being received. This is a problem.

If we, as teachers, are going to use rubrics to provide students with feedback, then that feedback needs to be packaged in such a way that it will not only be received by students, but it will also have an effect on student learning behavior.

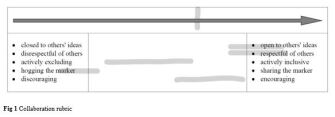

So, I began a process of successive design, modification, and testing of various rubrics in hundreds of classrooms. The goal was simple—find a more communicative rubric. What emerged out of this experimentation was two rubrics, the first of which proved to be optimal for communicating student competencies such as perseverance, collaboration, willingness to take risks, etc. (see Figure 1).

This rubric differs greatly from the typical four-column rubric in three specific ways.

1) Whereas typical rubrics tend to look for competencies in student work, this rubric looks for competencies in student actions. That is, it is an observational rubric to be used by the teacher while students are working—not after they are finished working.

2) When I interviewed students about the four-column rubrics, we heard things like:

Researcher: So, what do you need to improve on for next time?

Toby: I don’t know.

Researcher: Why not?

Toby: Like, sometimes I feel like I am “mostly right,” but my teacher thinks I “might have some errors.”

Toby’s statements of “mostly right” and “may have some errors” are in reference to the language used in a particular four-column rubric. Even if he wanted to improve, how does Toby make use of the feedback that he might have some errors to improve to being mostly right? It turned out that we cannot nuance language well enough to communicate differences between four columns. The bigger problem is that we think we can. In truth, however, that nuancing garbles the feedback for students, and they respond by not looking at it. The rubric above dispenses with this nuancing.

3) The headings at the top of each column have been replaced by an arrow. Interviews with students revealed that many of them were seeing the headings in the initial rubric as descriptions of who they are (fixed mindset), rather than where they are (growth mindset). By replacing this language with the arrow, students can’t avoid but seeing the feedback as a description of where they are.

Together, these three major changes made the feedback accessible and meaningful to the students, and, as a result, we saw massive changes in competencies like collaboration.

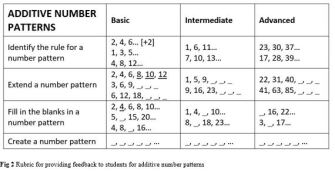

Whereas the rubric above proved to be most useful for communicating and shaping how students are performing on competencies, an altogether different rubric emerged for providing feedback on how students are performing on content (see below).

In order to be able to navigate, by land or by sea, you need two pieces of information—where you are and where you are going. Likewise, if we want students to be able to navigate their learning—to participate in their learning—they need to know where they are and where they are going. The rubric in Figure 2 does just this. By breaking a specific learning outcome into basic, intermediate, and advanced examples, students cannot only see where they are (either by your feedback or their own), but they can see examples of what they still need to learn.

When these types of rubrics were implemented in classrooms, we saw a 10-15 percent improvement in 50-70 percent of the students. When the feedback was received, students were able to change their learning behavior.

Design & Feedback

Julia Stearns Cloat, Ph.D., has spent the past 25 years working in unit school districts in roles including literacy specialist, instructional coach, and curriculum director and has earned awards for her work in student services. Julia currently works as a coordinator in Kaneland School District 302, in Illinois, and as an adjunct professor at Northern Illinois University:

Providing students with targeted and actionable feedback has proved to be an extremely effective instructional practice. In fact, according to (2020), effective feedback is equivalent to eight months of instruction per school year. When used as a tool for targeted feedback, rubrics can be an effective assessment tool. Following a few key steps will increase the effective use of rubrics.

Design

- Identify the specific learning targets to be measured. Keep in mind what you are assessing and leave off anything such as “presentation” that is not being assessed.

- Rubrics should be objective. Subjective terms such as “creative” will not give your students a better understanding of your expectations and rarely correspond to the standards and learning targets being measured.

- Avoid specific quantities. In attempts to make rubrics a gradation of specific expectations, teachers will include qualifying terms (e.g., 0-1 grammatical errors, 2-3 grammatical errors). On the surface, gradations of expectations such as this seem specific and measurable, but in reality, not all errors are equal in their impact on the final product.

- Consider having the students design the rubric. Divide students into small groups and give each group one target or standard to be assessed. Students will become more familiar with the standards and the expectations as they develop the criteria for success.

- Identify the specific learning targets to be measured. Keep in mind what you are assessing and leave off anything such as “presentation” that is not being assessed.

Feedback

- If using a teacher-created rubric, make sure the student understands the rubric before beginning the project or assignment. You may want to even provide exemplars and have the students assess them to ensure that they understand the expectations.

- As the students work on the project or assignment, use the rubric as a conferring tool. Give them specific feedback on their progress in relation to the expectations on the rubric. Depending on the project, you may want to focus on one criteria from the rubric at a time. Students may be overwhelmed with receiving feedback about every aspect of a large project all at once.

- Consider using the rubric as a self-assessment tool over time. Post criteria for the target or standard being learned alongside exemplars of each gradient of success. Students will be able to compare their current progress with the exemplars and have a clear understanding of what needs to be done to achieve the next level of success.

- When using rubrics for assessment, add actionable feedback and allow students to revise and resubmit their project or activity. This will provide students with opportunities to continue to learn.

- If using a teacher-created rubric, make sure the student understands the rubric before beginning the project or assignment. You may want to even provide exemplars and have the students assess them to ensure that they understand the expectations.

Thanks to Chris, Peter, and Julia for their contributions!

Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at lferlazzo@epe.org. When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at .

�����ܹ���̳ has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled .

Just a reminder; you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via (The RSS feed for this blog, and for all Ed Week articles, has been changed by the new redesign—new ones are not yet available). And if you missed any of the highlights from the first nine years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below.

I am also creating a .