Feedback is one of those words that teachers and school leaders (i.e., principals, head teachers (U.K.) love and hate at the same time. I say that because there is no doubt about the importance of feedback, because Hattie and Timperley found that it is one of the most effective influences on student learning (2007). However, what most educators do not like about feedback is how it is used against them. For example, feedback is often the purpose of walk-throughs, learning walks, and formal observations, but all too often the content of the feedback focuses on an area that teachers and school leaders never discussed beforehand, or the school leader lacks the credibility to provide feedback in the first place.

In a study of over 400 teachers and 4,000 students, Dawson et al. (2018) found that there are four reasons students and teachers believe are the main purposes of feedback: justifying grades, identifying strengths and weaknesses of work, improvement, and affective purposes.

A great deal of the feedback literature focuses on feedback to students, but what inspired this post was the idea that most of that literature was conducive to feedback between teachers and school leaders as well.

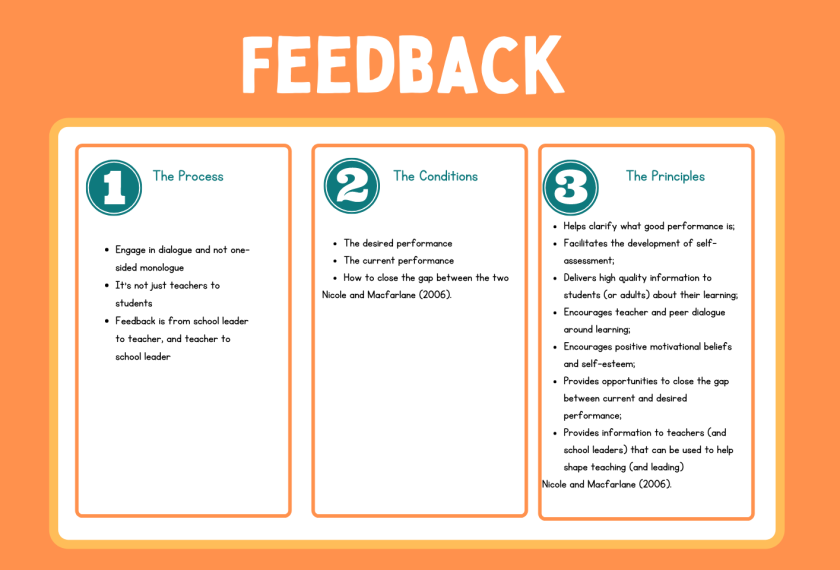

There are three ways to get feedback between teachers and school leaders right.

Feedback is a process, not a one-sided message

The first way to get feedback right is to look at it as a process and not a one and done event to tick off a box. Too often, walk-throughs, learning walks, and formal observations are seen as something to get done as opposed to a process to engage in that could be truly impactful to everyone involved. When we look at feedback as something to get done, we miss a great learning opportunity. In Dawson’s study, the researchers asked what made the feedback experience effective, and the prominent themes were, “the content of the comments, aspects of the feedback design and the source of the feedback information.”

Additionally, Dawson et al. (2018) write that, “The early 2010s marked a shift in how feedback was positioned within the literature, with understandings of feedback moving from something ‘given’ to students towards feedback as a process in which students have an active role to play.” When reading the research on feedback, as well as the above quotation, it makes me think of the feedback often given between teachers and school leaders. If teachers are expected to look at feedback as a process, and not something they just give to students in isolation, shouldn’t feedback be seen as a process between school leaders and teachers, too?

After all, Robinson (2001) looked at the organizational-learning (how an organization learns together) research by Argyris and Schön, and she writes that there are two strands by which an organization learns, which are:

- Descriptive strand—Has its roots in social and cognitive psychology, seeks to understand the processes by which organizations learn and adapt.

- Normative strand—Is sometimes referred to as research on the “learning organization,” is concerned more with how organizations can direct their learning in ways that bring them closer to an ideal.

The feedback process certainly can help the adults in a school achieve those two goals.

Three conditions necessary for effective feedback

The second way to get feedback right is by understanding the conditions necessary to provide effective feedback. Nicole, D. & Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006) suggest three conditions that must be clarified for anyone to benefit from feedback. In fact, in a recent review of feedback models, Lipnevich and Panadero (2021) refer to the study by Nicole and Macfarlane-Dick as “one of the most important readings in the formative assessment literature.”

The three conditions Nicole and Macfarlane highlight that are necessary to benefit from feedback are:

- The desired performance

- The current performance

- How to close the gap between the two

Where teachers and school leaders are concerned, I believe the three conditions highlight the importance of feedback being seen as a process and not a “one and done” activity. For this to happen, teachers and leaders would have to have a common understanding of the desired performance, as well as a clear understanding of the current performance. To be clear, these conditions should not be seen as top-down from school leaders to teachers. The reality is that any credible school leader would be asking teachers and students what they want out of a school leader and have a clear understanding of their current performance as a school leader.

What makes the third condition so difficult for the relationship between teachers and school leaders is whether either one truly knows how to close the gap. It is yet another reason to look at feedback as a process, because through faculty meetings that focus on learning instead of management tasks and instructional-leadership team meetings that focus on how and what leadership teams learn together, as well as effective professional learning communities PLC, can a school community truly engage in a feedback process that is worthwhile? In these learning sessions that take place at the faculty meeting, leadership-team meetings, or PLC’s, educators can discuss what Dawson et al. refer to as, “the content of the comments, aspects of the feedback design and the source of the feedback information.”

In education, we commonly hear that we need to be lifelong learners, and for that to happen, feedback in schools needs to be seen as an effective way to inspire self-regulated learning on the part of students, teachers, and school leaders alike. This leads us to the third way to get feedback right.

What inspires self-regulated learning?

In order to get feedback right, the third way to approach it is through understanding that there are seven feedback principles. Nicole and Macfarlane (2006) go on to write that those seven principles that influence self-regulated learning:

- Help clarify what good performance is (goals, criteria, expected standards);

- Facilitate the development of self-assessment;

- Deliver high-quality information to students (or adults) about their learning;

- Encourage teacher and peer dialogue around learning;

- Encourage positive motivational beliefs and self-esteem;

- Provide opportunities to close the gap between current and desired performance; and

- Provide information to teachers (and school leaders) that can be used to help shape teaching (and leading).

In the End

Over the last decade or longer, we have heard so much about feedback. At first, the word “feedback” was like our favorite song that we wanted to hear all the time, but then somewhere along the way, feedback became the song we no longer wanted to hear. Some of that was due to the fact that teachers and school leaders lack a common language and a common understanding of what feedback is all about.

If we are to show our school communities, and the rest of the world for that matter, that our schools are more than child care during the day and that school leaders and teachers engage in learning that is equally as powerful as the learning students are supposed to engage in, then we have to understand what feedback is all about and how it can be impactful.

Maybe it’s time to give feedback another chance.

Citations

David J. Nicol & Debra Macfarlane‐Dick (2006) Formative assessment and self‐regulated learning: a model and seven principles of good feedback practice, Studies in Higher Education, 31:2, 199-218, DOI:

Hattie, J., and H. Timperley. 2007. “The Power of Feedback.” Review of Educational Research 77 (1): 81–112.

Lipnevich, Anastasiya A. and Panadero, Ernesto (2021). A Review of Feedback Models and Theories: Descriptions, Definitions, and Conclusions. Frontiers in Education. Volume 6.

Phillip Dawson, Michael Henderson, Paige Mahoney, Michael Phillips, Tracii Ryan, David Boud & Elizabeth Molloy (2019) What makes for effective feedback: staff and student perspectives, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 44:1, 25-36, DOI:

Robinson, V.M.J. (2001), “Descriptive and normative research on organizational learning: locating the contribution of Argyris and Schön,” International Journal of Educational Management, Vol. 15 No. 2, pp. 58-67.