(This is the second post in a four-part series. You can see Part One .)

The new question is:

What does math instruction look like in the age of the coronavirus?

The and second posts in this series will feature commentaries by New York City high school math teachers Bobson Wong and Larisa Bukalov. They are the authors of (Jossey-Bass, 2020) and recipients of the Math for America Master Teacher Fellowship.

Here is the second part of their commentary:

Assessing and Grading Students

Assessments and grades are necessary parts of our instruction. Well-designed assessments hold students accountable for instruction and measure their skills. Effective grades clearly communicate student performance to parents, students, teachers, and administrators.

Assessing Students

Under normal circumstances, we don’t limit ourselves to the traditional paper-and-pencil assessments. Trying to prevent cheating when students are working online from home—for example, by giving multiple versions of tests or forcing all students to take the test at the same time—raises everyone’s stress level, provides an inaccurate picture of student learning, and fails to address the cause of their cheating. Here are some strategies that we use to make online assessments more meaningful.

First, we talk to students about ethics. We discuss the harm that cheating can cause and the values encouraged by our families. We reassure them that we are focused on improving their learning. These conversations are particularly important when students can use mobile apps like Photomath to answer math questions.

Nowadays, we use traditional test questions mostly to determine students’ prior knowledge or to modify our instruction. Online summative assessments should emphasize synthesis and self-reflection instead of recall and calculation. Open-ended questions are less likely than repetitive worksheets to encourage cheating. Students can assemble a portfolio that shows their growth over time. Projects enable students to showcase talents that they don’t often use in class.

Assessing student thinking has become more difficult as we teach remotely. Many of our usual techniques, such as cooperative activities or reading students’ body language, are difficult to do online. Instead, we allow students to reflect on their learning periodically by answering questions like:

- How would you rate your learning this week? Explain.

- Summarize your favorite lesson from this week. Explain why you liked it the most.

- How can I improve your online learning?

We assign these questions as homework or quizzes. However, we emphasize that we grade them based on the honesty and thoughtfulness of their response, not on what they think we want to hear.

Grading Students

Quantifying grades under normal circumstances is hard enough, but trying to do so under extraordinarily stressful circumstances is cruel.

In times like these, we believe that giving pass/incomplete grades is fairer than numerical or letter grades. We don’t know if students aren’t completing work because they don’t understand the lesson, they lack a quiet place at home, or they have limited internet access. When possible, we prefer to give students the benefit of the doubt. Of course, simply giving students more time won’t address the inequity they face, but it allows us to reach out to families and see what we can do to help them.

We find that grading online generally requires more time than grading papers. Files take time to load onto our computers, and reading them on a small screen means more scrolling and zooming in. Thus, we budget more time for us to grade, which forces us to reduce our workloads in other areas.

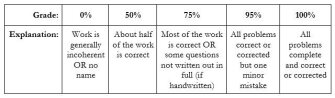

To simplify grading, we emphasize scoring that encourages students to correct mistakes and reflect on their work. We review classwork questions in our online meetings so that students can see what they did wrong. We grade work using the scoring guidelines below:

In times like these, assigning the right grade is less important than providing meaningful feedback. Positive feedback that praises students’ effort (“This is a clever solution”) can strengthen students’ growth mindset by suggesting that hard work will help them improve.

No matter what grading system we use, we emphasize to students that their grades don’t fully capture what we think about them or what they have learned. We acknowledge their humanity whenever we can by praising them when they make progress or encouraging them when they face setbacks. In times like these, such encounters make a more memorable impact on students than the grade we give them.

Caring for Others and Ourselves

Under normal circumstances, many teachers work alone—separated by classrooms from their peers. During a crisis, teachers can often feel even more isolated. Maintaining a sense of balance for us and connecting with the people around us can be especially challenging.

Helping Students

During this crisis, we’ve heard countless stories of grief from our students. They’ve told us about family members who have lost their jobs or lives, as well as their own feelings of depression. English- language learners and students with learning differences face even greater challenges since many of them lack the social-emotional and academic support that they received in school.

To help, we try to take some time each day to reach out to individual students. If appropriate, we give students more time or suggest alternatives. If necessary, we arrange online meetings with students so we can talk. These virtual connections can provide valuable support for everyone.

Helping Families

Parents and other caretakers can be just as overwhelmed as students. Like us, they have to work from home while managing their children’s online learning, effectively turning them into home school teachers.

In times like these, we try to reach out to as many parents as we can, using whatever methods are available to us. We find that many of them are relieved to talk to another adult! For parents who don’t understand English, we try to get translators to help us. An online translation tool like Google Translate can be a last resort.

We make a special effort to communicate with the parents of students who are not submitting work. We avoid using confrontational language that could be misinterpreted as accusatory or judgmental. Instead, we express concern for the student, offer positive comments, state our concerns, and suggest specific action.

Connecting with Other Educators

Normally, we collaborate frequently with teachers and other school staff. This collaboration can include sharing lesson plans, observing each other, or writing assessments or other assignments together. In times of crisis, most of us are cut off from daily interactions with colleagues, making collaboration much more difficult.

To stay connected with other educators, we communicate regularly with them using emails, phone calls, text messages, or online meetings. Staying in touch can help relieve stress and give us valuable ideas for teaching. In fact, most of the ideas that we discuss here came from talking to other teachers!

We also use social media to communicate with other educators. Online communities like the Math Twitter Blogosphere (#mtbos) and I Teach Math (#iteachmath) on Twitter include teachers, administrators, and professors from around the world.

In addition, many academic conferences that have been canceled due to the pandemic are experimenting with online sessions. For example, the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics is hosting free webinars that would have been held at its Centennial Annual Meeting in Chicago (). Other local, state, and national organizations have similar offerings online.

Taking Care of Ourselves

Most importantly, we constantly tell ourselves and others in times of crisis that teachers don’t need to do everything to succeed. Setting emotional and physical boundaries is especially important when working from home since there we literally cannot get away from teaching.

In order to prevent our work from consuming us, we set limits on our work. We only respond to work-related calls and messages during certain hours, leaving nights and weekends for family and other personal matters. During workdays, we set up a schedule, setting aside at least 10 minutes per hour for breaks. After lunch, we take an extended break from our computer screens. If possible, we take a walk to get our exercise. If we have family at home, we also plan time during the day to spend time with them.

Sometimes, despite our best efforts, we find ourselves overwhelmed by the loss of instructional time, personal freedom, social gatherings, and the health of loved ones. At these moments, we remind ourselves that the grief that we are experiencing can leave us exhausted and less focused. Recognizing that we can’t do everything and taking time to pause and reflect can often be a source of strength.

Thanks to Bobson and Larisa for their contribution!

Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at lferlazzo@epe.org. When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at .

�����ܹ���̳ has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled .

Just a reminder, you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via or And if you missed any of the highlights from the first eight years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below. The list doesn’t include ones from this current year, but you can find those by clicking on the “answers” category found in the sidebar.

I am also creating a .