Visitors to Anchorage’s Turnagain Elementary School are more likely to hear pupils greet them with “Kak de-LAH” than “How are you?” They’d be well advised to respond with “nee-PLOH-hah” (not bad), and if they’re curious, politely ask their host’s name: “Kahk-vahz-zah-VOOT?”

Those phonetic introductions would no doubt befuddle many adults, but they’re growing more natural by the day at Turnagain, which advocates of foreign-language study say has one of the only Russian-immersion programs at a public elementary school in the United States.

The initiative, which began in the fall, is run through two classes in 1st grade and two in kindergarten, where children spend half the day learning entirely in Russian and half in English. Over the coming years, the 49,000-student Anchorage district plans to expand the program to higher grades, year by year, so that students can continue to build on that early language base.

Today’s translation and conjugation drills will yield rewards in the long run, district officials believe. They point to the belief that pupils’ early learning not only boosts their chances of becoming fluent in those languages, but it also can strengthen their performance in other subjects.

Immersion Uncommon

Study of Russian language and culture gained ground in American schools during the early stages of the Cold War, as suspicion and competition between the United States and the Soviet Union intensified. Interest soared after the Soviet launch of Sputnik 1 in 1957, when U.S. government and school leaders particularly saw increased knowledge of Russian as a national-security necessity.

Today, Russian is the sixth- or seventh-most-popular language taught in K-12 schools, foreign-language advocates say, with most of the courses being offered at the secondary level. Russian ranks well behind Spanish and French, with a place comparable with that of Chinese or Italian.

Russian classes at the elementary school level are even less common. A survey conducted in the late 1990s by the Center for Applied Linguistics, a nonprofit group in Washington that promotes the study of language and culture, found that only 1 percent of public and private elementary schools in the United States taught Russian, down from 2 percent a decade earlier.

Foreign-language experts know of only a handful of Russian programs in public elementary schools that would qualify as “immersion” initiatives, using models similar to Turnagain Elementary’s. Still, those in-depth approaches make sense, given the difficulty of mastering the language, which has its own alphabet, among other hurdles, said Jane W. Shuffelton, the president of the American Council of Teachers of Russian. Her group is a division of the Washington-based American Councils for International Education.

“If you want to get to real proficiency, it takes a long period,” said Ms. Shuffelton, who teaches Russian at Brighton High School in the 3,400-student Brighton Central school system in New York. “It takes more hours of study.”

Roots in the Motherland

Russian-language programs tend to be strongest in regions such as the East Coast, where immigrants from Russia have a strong base, Ms. Shuffelton noted. In Alaska, though, Russian influences trace back hundreds of years, when Slavic explorers established villages, forts, and churches across territory that would be purchased by the United States in 1867 and would later become the 49th state. Anchorage has a well-established Russian community, with roots that include businesses and neighborhoods near Turnagain Elementary School, said Elena Farkas, a Russian-language resource teacher with the district.

“There was a very strong demand for [a language program] in the community,” said Ms. Farkas, a native of the Siberian city of Magadan. Not surprisingly, some Russian-American families see Turnagain’s program as a way of helping preserve their heritage, she said. “Lots of children are losing the language,” she said. “The schools can maintain that interest.”

Anchorage’s efforts to establish a Russian-immersion program at the elementary level date back more than a decade, Ms. Farkas said. The current venture at Turnagain Elementary, which serves prekindergartners through 6th graders, was buoyed by a grant worth nearly $500,000 from the U.S. Department of Education’s foreign-language-assistance program, which began during the 2002-2003 school year. The immersion program is optional. Seventy out of the school’s 351 pupils participate, and because of its popularity, students are selected through a lottery.

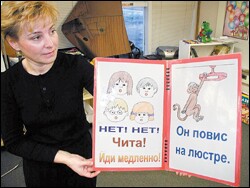

The program is taught by two natives of Russia, both of whom are certified in elementary education in Alaska. Each day, students are taught math, science, and some language arts and alphabet in Russian, for a period lasting roughly three hours. They study reading, writing, and social studies in English, along with a review of math. Students outside the immersion program also receive Russian-language training, albeit on a more limited scale.

The language lessons extend beyond the classroom. Signs in Turnagain’s hallways are printed in both English and Russian, and school announcements are given in the two languages. Lessons on Russian history and culture are blended throughout daily studies.

“They learn the language like it’s their native language,” Ms. Farkas said of pupils at the school. “For them, it’s so natural. They absorb it as a different way to speak.”