Faced with arguably the biggest crisis of its 155-year history—the loss of at least 100,000 full-time members—the nation’s largest union plans to respond by organizing thousands of new members and transforming itself into an even more politically potent force.

Whether the National Education Association can accomplish those goals while simultaneously advocating improvements to the teaching profession—a role publicly supported by its leaders, but contested among the rank and file—remains an open question.

Nothing less than the organization’s future appears to hinge on the answer.

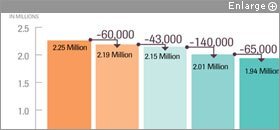

Since 2010, the teachers’ union estimates, the NEA has lost the equivalent of 100,000 full-time members, bringing its overall numbers to approximately 3 million educators. By the end of its 2013-14 budget cycle, the union expects it will have lost 308,000 full-time members and experienced a decline in dues revenue projected at some $65 million in all.

“There is no question that we have to change. That’s already been decided for us,” the union’s secretary-treasurer, Rebecca Pringle, said here this month at a hearing on the union’s strategic plan and budget, during which its drastic membership losses were disclosed. “The question is, are we going to manage our decline, or are we going to find that path forward?”

SOURCE: National Education Association

Even former NEA executives see the road ahead as a delicate one.

“The public-sector unions are in panic mode; all the attacks have made politics a high priority,” said John I. Wilson, a former executive director, who writes an . “In a way, they’re focusing where they need to be, but at the same time, they need to be readying for how they are going to utilize friendlier politicians, and quite frankly, make new friends to move an education agenda that is of service to the country.

“If you don’t couple politics hand and hand with professional issues,” Mr. Wilson concluded, “then your members lose.”

Staff Losses

The newly approved NEA strategic plan and budget, approved at the union’s annual Representative Assembly, held July 2-5 in Washington, opens with a preamble stating bluntly that “things will never go back to the way they were.”

The union has not released state-by-state affiliate numbers for 2011-12, but interviews with a handful of state leaders suggest that those states that have faced hostile legislation have been among the affiliates experiencing losses.

Mary Bell, the president of the Wisconsin state affiliate, said about a third of its local affiliates are now subject to the terms of a high-profile 2011 law outlawing bargaining over issues other than wages pegged to the rate of inflation. (The others negotiated new contracts before the law took effect.) The union has managed to keep about 70 percent of the collective membership of that third as members, she said.

The union had around 90,000 members before the law was enacted.

In Tennessee, where collective bargaining was replaced in 2011 with “collaborative conferencing"—a policy that gives unions merely an advisory role in setting work rules—the union has seen a 10 percent decrease in membership, or more than 4,500 individuals, said Tennessee Education Association President Gera L. Summerford.

Budget woes have also taken their toll on the national headquarters. To avoid unnecessary layoffs, the NEA offered an early-retirement incentive for management and staff members in a bid to pare its payroll. Fifty-six individuals—about a tenth of the NEA’s workforce—took advantage of the incentive, according to sources in the union. Another 14 officials in management roles were either reassigned, asked to reapply for other positions, or dismissed.

The union also cut some benefits for both managers and staff, such as the matching component of a supplementary 401(k) retirement program. That unusual move was one of several contributing factors that nearly occasioned a strike by the NEA’s own internal staff union.

Coupled with a slimmed-down staff, the union has also combined some of its internal divisions, cut the number of conferences and meetings requiring travel, slimmed its publications, pared general-membership communications, and scaled back programs for training minority and women union leaders.

Cuts to those programs drew some complaints from their constituents over the course of the union’s convention. But some NEA staffers said privately that they believed the consolidations were long overdue.

“It’s basically forcing them to do things that probably should have been done years ago,” said one union staffer, who, like others interviewed for this story, spoke on the condition of anonymity.

Political Context

The drastic slide in the NEA’s membership reflects a rapid change in the political and policy context over the past four years.

Ms. Pringle pointed to a “trifecta” of factors contributing to the membership losses: the economic recession and its aftermath that cost thousands of teachers their jobs; attacks by Republicans on public-sector unions; and, as she put it, changes ranging from “stupid education ‘reform’ to an explosion in technology” that have rapidly altered teachers’ job descriptions.

The NEA was among the groups that championed $100 billion in federal stimulus aid for education that helped many teachers maintain their positions, as well as a supplemental $10 billion specifically earmarked for education jobs. But the stimulus money brought with it Obama administration initiatives unpopular with teachers’ unions, such as the Race to the Top program, which emphasized teacher accountability and performance pay, ideas more traditionally associated with Republicans.

In 2011, after big GOP gains in the midterm elections, came disastrous events from a union perspective: a spate of attacks on collective bargaining from Republican-led legislatures, some apparently emboldened by the tough talk from Democratic leaders on education. Five states—Idaho, Indiana, Ohio, Tennessee, and Wisconsin—passed laws curbing or outlawing collective bargaining for teachers. (Ohio’s was later overturned in a referendum.)

The sum total of those events has thrust the NEA into a dramatic, and at times disconcerting, shift in priorities, according to sources in the union’s Washington headquarters, who detect in the recent staff reorganizations a desire to reshape the union into even more of a political heavyweight—one focused primarily on electing labor-friendly politicians.

The union has been a powerful political force in the United States for decades, but its roots as a professional association have kept it somewhat removed from other labor coalitions that have historically served as the backbone of the Democratic party.

“The leadership wants to be politically more influential than in the past, to be recognized for the things that the AFL-CIO has been known for—troop movements,” said one official who works at the union’s headquarters. “The problem is that NEA is a huge organization, and most members care about more than politics.”

Added another internal source: “They are very focused on electoral politics, and I think there are people who didn’t necessarily sign on for that.”

The officials attributed the newfound focus in part to the union’s new executive director, John Stocks.

Since assuming the job last September, Mr. Stocks has overseen much of the reorganization and has hired a new senior communications director, Ramona Oliver, whose experience includes representing such Democratic-leaning groups as the Service Employees International Union and EMILY’s List, a prominent political action committee.

An emphasis on electoral politics was certainly on display at this year’s Representative Assembly, which was difficult at times to distinguish from a campaign rally. A photo of NEA President Dennis Van Roekel with President Barack Obama hung close to the doorway of the convention hall. A banner fashioned out of white butcher paper was festooned with supportive notes to the U.S. president written by delegates.

And Mr. Obama was at the heart of Mr. Van Roekel’s address to the more than 7,000 delegates.

“We can’t set education policy by ourselves, but we do have the power to influence it. And first on the list—we must do everything we can to re-elect President Barack Obama,” the NEA president said.

The union’s newly approved budget also outlines its road map for invigorating membership numbers. It has created a new Center for Organizing and plans to put some $200 million specifically into organizing members between 2012 and 2014, the single largest line item in the budget.

“Probably the most significant and most important change in the organization is a re-emphasis after many years on organizing members,” Mr. Stocks said in an interview.

He said the NEA will pay particular attention to engaging younger members and helping them assume leadership of the union from baby boomers, who form the majority of members. “We are essentially an organization in transition from two very significant generations,” Mr. Stocks said.

Some of the organizing could be helped by an increase in the percentage of dues money the national union returns to its state and local chapters.

State affiliate heads said they are eager to begin the work, but acknowledge that organizing has not been a strong point. That’s in part historically due to state mandatory-bargaining laws, exclusivity provisions, and no-raid agreements with other unions that have minimized the need for aggressive action.

“We’ve done some training on organizing in the field, but we recognize that it’s labor-intensive,” Ms. Summerford of the Tennessee state affiliate said of her union’s new activities in this area. “It means a lot of face-to-face contact with members and potential members.”

Ms. Bell of the Wisconsin Education Association Council said affiliates will need to be far more purposeful in explaining the benefits of membership. “You want to make sure that you make the value proposition to your members everywhere,” she said. “When they are actively making decisions [about joining], ... you’re very attentive to exactly what that value proposition is.”

Some observers believe the NEA should push more forcefully on using its position to set—and hold members to—higher standards, thus boosting the cachet of membership.

“Do I want to join an organization where I know that’s where the good teachers are, or the one that people join because they think they’re going to get into trouble?” said Mr. Wilson, the former NEA executive director. “People don’t join because of the politics. That’s the means, it’s not the end. If the unions don’t show what’s the end in political action, they won’t get the buy-in.”

Familiar Tension

The union’s newly approved budget also indicates a desire to lead on such professional issues, though the amount it will spend developing those plans, $22 million, is only a quarter of the $87 million it will spend on strengthening its affiliates. Still, Mr. Van Roekel, who renewed attention on teacher quality over the course of his tenure as president, made a point of mentioning its importance during the Representative Assembly."It’s not enough to say that most teachers are good. If there is even one classroom with a teacher who isn’t prepared or qualified, we can’t accept that,” he said during his speech to delegates.

Several of the NEA’s affiliates, partly under political pressure, have been willing to strike deals on teacher-quality issues that would have been unthinkable a few years ago. The Massachusetts affiliate, for instance, negotiated with lawmakers and the Stand for Children advocacy group on a bill that gives performance the edge over seniority in layoff decisions.

And a handful of local affiliates, such as the and Springfield, Mass., chapters, have begun to explore the concept of labor-management collaboration.

But there were also signs during the convention that rank-and-file members are still hesitant to take on such topics as evaluation and professional development, long seen as the task of management. For instance, delegates defeated a resolution that would have called on the union’s UniServ directors to help advocate on behalf of the educational issues outlined in a report by an NEA-commissioned panel in December. (UniServ, the union’s regional-support program, has traditionally helped affiliates, especially smaller ones, with contract negotiations and grievances.)

Delegates speaking against the motion argued that it would weaken the union’s ability to respond to bread-and-butter issues during a time of crisis.

“We don’t need to reinvent UniServ as a cadre of teaching and learning experts,” one delegate protested.