Thereãs nothing unusual about the lessons being presented in Janet Floydãs high school algebra class: quadratic equations, square roots, and fractions. Whatãs less familiar is the amount of time spent on that material: one hour and 36 minutes, every day.

The extended-length course at Mount Pleasant High School, part of a program known as Tiger Academy, is required of students who failed the math portion of the Texas state assessment.

School officials here launched the venture four years ago in the hope that doubling the amount of class time on core academic subjects would raise student achievement and test scores. Similar strategies are being used in schools across the country, especially in reading and mathematics, where lengthier classes at all grade levels are becoming increasingly common.

In Mount Pleasant, the double-dosing, which occurs in reading, math, and science, was partly an acknowledgment that other remedies, such as extra tutoring and summer school, simply werenãt giving teachers enough time to address the particular demands of their student population.

ãI like the fact that Iãm taking kids who are saying, ãI canãt do it, I hate math,ã and just building their confidence,ã said Ms. Floyd, who teaches Algebra 2. ãThe extra time helps a whole lot. ãÎ Iãve been able to build a relationship with them.ã

Research has shown that increasing ãtime on taskã has a positive effect on student learning. But recent pressure to raise reading- and math-test scores under the federal No Child Left Behind Act has led more schools to pursue that approach.

Others factors are also at work. Two federal grant programs to improve the performance of struggling readers, Reading First and Striving Readers, encourage schools to consider longer class periods in that subject.

In addition, some states have sought to carve out more time for core subjects. Florida requires many struggling elementary school readers to spend at least 90 minutes a day in the subject. California requires applicants for federal Reading First grants, which apply for money through the state, to agree to spend 2ô§ hours a day on language arts in grades 1-3.

ãThe thought is, the greater the need, the more time you need in intensive instruction,ã said Mary Laura Openshaw, the director of Just Read, Florida!, the stateãs reading program. ãThe student needs should drive the course schedule.ã

Gains and Sacrifices

In many schools, however, increasing the time spent on core academic subjects requires cutting other classes. Mount Pleasant students must give up one elective each year they double-dose. The high schoolãthe only one in the 5,200-student district, located about two hours east of Dallasãlimits students to one double-dose class per year, in part to spare other electives.

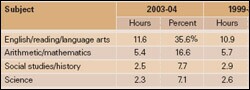

Public school teachers in grades 1-4 increased the time devoted to reading and math from the early 1990s to 2003-04.

*Click image to see the full chart.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Education

Students are assigned to Tiger Academy based on their previous yearãs scores on the Texas Assessment of Knowledge and Skills. Those who flunk more than one section are assigned to academy classes based on which section district officials believe they are closest to passing. Starting in 11th grade, students must pass TAKS subjects in math, reading, science, and social studies to earn a traditional high school diploma.

Researchers and educators have long questioned whether cutting optional courses, while ratcheting up demands in core subjects, causes students to lose interest in school. A survey of high school dropouts released earlier this year found that they reported being more likely to stay in school if their classes were more engagingãbut also if more was demanded of them. (ãH.S. Dropouts Say Lack of Motivation Top Reason to Quit,ã March 8, 2006.)

Lack of skills in reading and math is a major factor that drives students out of school, said Bob Wise, a former governor of West Virginia. Doubling instructional time in those areas makes sense, especially in the early grades, but schools must also be committed to finding innovative ways to keep those subjects interesting, said Mr. Wise, now the president of the Washington-based Alliance for Excellent Education, a research and advocacy organization focused on low-performing secondary students.

ãIf all you do is take one reading period and make it into two,ã the Democrat said, ãindeed you lose them.ã

Betsy Brand, the director of the American Youth Policy Forum in Washington, said cutting out all electives from the school day is a ãterrible idea.ã Schools can add instructional time in reading and math and keep students engaged by integrating other topics such as career-oriented lessons into those core classes, said Ms. Brand, whose nonprofit organization examines youth education and workforce issues.

ãItãs awfully hard to do reading and math in isolation without applications that make it real for kids,ã said Ms. Brand, an assistant secretary for vocational education under President George H.W. Bush.

In Mount Pleasant, school leaders saw double-dosing as a way to raise achievement within a fast-changing student population that needs extra help with the English language. The district has seen an influx of Latino families in recent years. Today, 45 percent of the high school students are Hispanic, many of whose families were drawn to the area by jobs.

Time for Review

Mount Pleasant officials first heard of the potential of double-dosing at a conference organized by the Southern Regional Education Board, a research and policy organization in Atlanta, where they learned of its positive effect on student achievement in other districts around the country.

Since the district launched its initiative, Mount Pleasantãs state test scores have improved, though district officials acknowledge they still fall short by some measures. The districtãs TAKS scores have steadily improved in math and science, and until 2005, the most recent recorded year, in language arts. But in 2005, the district did not make adequate yearly progress, a key measure under the No Child Left Behind law, among two subcategories of students in language arts: black students and those with limited English proficiency. District dropout and attendance rates, meanwhile, as reported to the state, have held steady since the academy was founded.

Tiger Academy classes are held in the same building as other Mount Pleasant High courses. About 30 percent of the schoolãs 1,300 students take at least one academy class. Although district officials could not provide a separate breakdown of TAKS scores for the academyãs students, individual teachers report progress. None of the students who entered Ms. Floydãs 2005-06 academy classes had passed the 10th grade math TAKS. The teacher estimated that 70 percent of those same students passed the 11th grade exam.

The academyãs two-period classes give teachers more time for one-on-one instruction and for review of difficult material, she says. The second 48-minute period enables her to present difficult math in different ways, such as through group activities and games.

ãI never have more time than I need,ã Ms. Floyd said. ãI always use the time up.ã

Sometimes she uses visual aids, such as a collection of small, square blocks, which students are asked to assemble in various shapes. The lesson helps build understanding of surface area and volume, a topic that vexes many of her students on the TAKS.

Double-dosing also enables academy teachers to address puzzling problems in unorthodox ways. Many teachers voice frustration over studentsã refusal to do homework. Some students receive little encouragement from parents, who often work late and arenãt there to prod their children, teachers say. The extra period allows teachers to devote some of that time for assignments that students would normally be expected to do at home. When possible, some academy teachers also avoid using their state-approved math textbooks, which their students find dense and confusing. Instead, the teachers craft their own, more focused worksheets and assignments.

Academy teachers address studentsã limited English skills in a variety of ways. Ginger Holt, a 10th grade geometry teacher, says she alternates between having students work individually and in small groups. Working in groups allows students with a weaker grasp of English to get the help they need; the stronger students, the teacher says, reinforce their skills through working with others.

During a lesson on graphing, one student, Pedro Ayala, speaks quietly in Spanish to a classmate at his table. When they come to certain conceptsãangle of elevation or angle of depressionãthey turn to English.

ãI say the easy stuff in Spanish,ã explained Mr. Ayala, a sophomore. When it comes to understanding what the concept means, ãyou can transfer it better,ã he added.

New Vocabulary

The 16-year-oldãs story is a familiar one at Mount Pleasant High School. Born in Mexico, Mr. Ayala moved to the United States to stay when he was in 3rd grade. His English has improved steadily, though certain words still trip him up, especially in math.

Passing the TAKS math exam will increase his odds of fulfilling his postgraduation goal: getting into an automotive-technology program. He does not expect the test to be easy. In addition to fractions, he says, word problems pose the biggest hurdle for him on standardized tests.

ãYou just have to go one word to another. Itãs hard,ã Mr. Ayala said. Itãs not unusual for a single word to stop him. ãProportion?ã the student recalls thinking the first time he read it. ãI donãt even know what that means.ã

Mount Pleasant Highãs eight-period day, staff members say, gives the school flexibility that schools with shorter days donãt have. The one elective that students in Tiger Academy must sacrificeãMr. Ayala, for instance, says he was not able to take an electrical courseãmeans they still get to keep at least one. A classmate could not take a music elective. A student in Ms. Floydãs class lost out on an optional criminal-justice course.

One of the main benefits of having that extra period with students is that it gives teachers more time to identify individual weaknessesãand makes students more comfortable talking about them with teachers, says Betty Geffers, who teaches a 10th grade English class in the academy.

Along with basic skills such as vocabulary and reading comprehension, she stresses studentsã writing. On this day, she asks them to compose a poem, providing autobiographical details and using specific phrases, such as ãI am a sibling ofã.ã Many students struggle with the assignment, she says, because they are not accustomed to writing with a voice, a task that is tested on the TAKS. To write creatively, students have to open up, Ms. Geffers says, and eventually, many of them do.

ãIf this were a single [period], you could not build that trust with kids,ã she said. ãIt gives them the opportunity to brag about themselves, and it allows them to be creative.ã