Public education in New Orleans has passed a quiet but important milestone: After more than a decade, all of the city’s public schools that had been taken over by the state of Louisiana after Hurricane Katrina are once again reunited under the local school board.

Starting this month, the Orleans Parish School Board will oversee a wholly unique system of autonomous charter schools, a transformation that was kicked off 13 years ago when flooding from Hurricane Katrina decimated the city. As the floodwaters receded, the state of Louisiana’s Recovery School District, the state-run district tasked with turning around failing schools in the state, took over most of New Orleans’ schools, many of which had been chronically failing for years. The RSD either shuttered them or handed them over to charter operators to run. Today, almost all of New Orleans students attend charter schools.

This has become the new normal in New Orleans. Today, nearly two-thirds of New Orleans residents believe charter schools have improved public education in the city, according to the most recent .

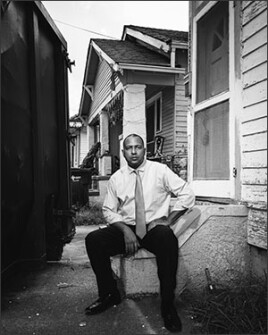

Patrick Dobard helped oversee the highly controversial process of closing and converting schools into charters as the superintendent of the Recovery School District. He is now the , an influential nonprofit that funds charters and other support organizations. We spoke about how far this experimental and utterly unique public-school system has come in the past decade.

The city’s public schools , according to research by the New Orleans Education Alliance, based at Tulane University. But it has also had its share of challenges, particularly in how the system handled student discipline .

The city continues to face challenges, Dobard acknowledged. Some 20,000 are still attending schools graded D and F in the state’s accountability system, Dobard said, as the city still grapples with creating enough high-quality schools. (This interview has been edited for clarity and length.)

Ed Week: What have been the city’s greatest gains?

Dobard: I think the academic growth of our African-American student population, which is a high-poverty population, has been incredible. Secondly, the college enrollment rates have skyrocketed, we don’t have great information, yet, on college completion.

In 2004, 37 percent of graduating seniors ... went onto post-secondary programs. In 2017, it’s 61 percent. And over the same time [period], for Louisiana, it was 47 percent in 2004 and 58 percent in 2017. In 2004, 1 in 4 [students] were graduating on time, now it’s almost 3 out of 4.

Those are some things from an instruction and academic perspective.

Several years ago, we created a , and it creates fairness and equity in enrollment. What we’re trying to figure out now is how to increase the number of high quality seats in the city.

We’re proud of the differentiated funding formula, where we weight our dollars that we distribute to schools based on the characteristics of the students they’re serving.

Ed Week: Let’s go back to on-time graduation rates. They have been on a downward slope over the past few years. What’s happening and how will that be addressed?

Dobard: It is a bit concerning, anytime you don’t continue to see the positive trends you’ve been seeing. I don’t think we’re going to see as much growth as we have in the past. The state has also, wisely, raised the standards in the last couple of years. Therefore, that has required schools to make shifts in curriculum and instruction, and I don’t think as many schools in New Orleans were paying as much attention to that as they should have.

I think it was the fact that, as the data I shared with you, we had grown so much, most of the test scores that we made were really in the first seven years of the reforms. In 2005, 33 percent of [New Orleans’] students were at or above grade level. In 2016 it’s 61 percent. The state went from 58 percent to 67 percent--a 25 percent gap to 6 percent point gap.

We have done a phenomenal job of closing the gap, but the standards have risen.

For now, it’s a good problem to have because we’ve seen so much growth, and it’s more challenging because I don’t think we’re going to see the large gains in such a short period of time again.

�����ܹ���̳: What are the city’s biggest challenges moving forward?

Dobard: I think there are like four of five things.

The majority of the kids we are dealing with in New Orleans are coming out of generational poverty. We have to break that cycle both inside education and outside education.

The second thing is that we’ve created this unique, decentralized system of schools, the only one of its kind in the nation, and we have to be clear about the roles of government of schools and communities as we move forward.

Authorizers don’t directly run schools. Along with that, another layer of government that is critical but a challenge for us, is the quality of membership on the boards that run charter schools. Whether it’s a [charter management organization] or a single-cite charter, they all have a board. They are the equivalent of the local school board for those families.

We have a number of partnerships that are strengthening the recruitment of our teachers. We have a lot of turnover. We are also starting to lose some of the first generation of founders of schools. And we have to do a better job around succession planning.

Those are some of the challenges we have to address.

�����ܹ���̳: Will New Orleans remain this island of school reform?

Dobard: I would hope that we don’t remain an island. But what I do encourage folks nationally to think about is, how can you create within your school districts true autonomous areas of school reform or school transformation, that can empower the people in the school buildings to make the decisions?

Short of having a natural disaster that has spurred people to be forced to do schools differently, how do you create spaces for true innovation to flourish and for bureaucracy to get out of the way?

Related stories:

Photo (top): The Bienville Elementary School building, in New Orleans’ Gentilly neighborhood, was taken over by First Line Charter Schools where Arthur Ashe Charter School now operates—Swikar Patel/�����ܹ���̳-File

Patrick Dobard, the former superintendent of the Recovery School District, outside his childhood home in New Orleans’ 7th Ward in 2015.—Edmund D. Fountain for �����ܹ���̳-File