Several schools aiming to better prepare students for a global economy and foster cultural understanding between the United States and China have turned to virtual exchange programs between American and Chinese schools.

“The global market is changing 24-7,” said William Skilling, the superintendent of the 4,600-student Oxford community school system in Michigan. “We feel it is mission-critical for every student to become fluent in a world language and fluent in multiple world cultures.”

To that end, the district hires only native speakers to teach foreign languages, hosts both virtual and physical exchange programs with Chinese students and educators, and launched an international school in China that will allow students from the district to study there.

“In today’s global market, you need to have the skill set by which you can have virtual meetings in which multiple languages and cultures are present at the same time,” said Mr. Skilling.

The international school, called the , in Shenyeng, China, will allow American students to spend up to three years studying at the school in China. Students in Oxford Community Schools will receive the first opportunity in this program, followed by students in Oakland County, where the district is located, before the program is opened up for students throughout Michigan.

Students will receive scholarships for the program but will be responsible for purchasing their own airfare, said Mr. Skilling. The school district will be offering 50 scholarships initially. Although the school was founded in April 2011, classes there will not start until next fall, Mr. Skilling said.

The school district has received financial assistance from the Beijing-based Hanban, a Chinese institution affiliated with the Chinese Ministry of Education, as well as the Confucius Institute at Michigan State University in East Lansing, to launch the school and support its Chinese education initiatives.

Establishing stable Internet connections in China has been one of the biggest challenges in setting up the school, he said. “It’s not that [Chinese educators] don’t have access to technology,” he said. “It’s more to do with the stability of the network.”

For the past three years, starting in kindergarten, students in the Oxford district have opportunities to learn synchronously and asynchronously online with their Chinese peers.

“They make videos, send them over, pose questions, and talk about different things they like in America,” Mr. Skilling said, referring to the Oxford students.

For the 2012-13 school year, the district will launch a foreign-exchange program in which high school students in Michigan will attend the district’s international school in China full time, at set classroom times, via the Internet. The students will take virtual classes, at the high school building, from 8 p.m. until 4 a.m.

“A lot of American students choose not to do exchange programs because they don’t want to leave their peer group,” Mr. Skilling said. This alternative will allow those students to have an international experience without leaving their families and friends.

The program will be officially announced this spring, said Mr. Skilling, and students will be allowed to sign up until the end of the school year in June. So far, no concerns have been voiced about a ‘graveyard shift’ education schedule, he said.

Beyond Stereotypes

The Oxford district has also sent more than 60 teachers to China to help them get a better understanding of the Chinese education system using grant money from Michigan State University’s Confucius Institute’s classroom grants, Mr. Skilling said.

“Our teachers have become much more aware of the culture, and they’re starting to get a little better understanding of the language,” he said.

However, virtual education in China has grown much more slowly than in the United States, he said.

“Virtual learning in China is just starting to take seed,” Mr. Skilling said. “Because it’s still something very new, there’s a hesitancy to jump on board with it.” (“Quality Concerns Slow E-Learning Growth in China,” this report.)

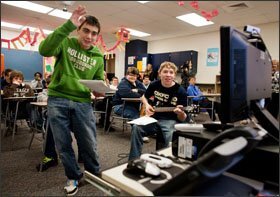

At the 2,300-student State College Area High School in State College, Pa., students in Susan Anderson’s learning-enrichment class are taking part in a virtual exchange program called set up through Schoolwires, an educational technology company based in the town.

Ms. Anderson collaborated with a teacher in the Beijing Yu Yuan Tan Middle and High School to launch a pilot of the program during the fall 2010 semester. The pilot began with 30 American 10th through 12th graders and 30 Chinese students; the classes used Schoolwires’ software to facilitate a cultural exchange between the two classrooms.

“The [American] students were shocked to find out that [the Chinese students] liked some of the same music, movies—that they actually watch some of the same TV shows,” said Ms. Anderson. “It certainly broke down a lot of the stereotypes.”

The first semester focused on allowing the students to get to know one another better, said Ms. Anderson. The American students created a FAQ page with answers to questions their Chinese counterparts were interested in, such as the college-admissions process in the United States.

The American and Chinese students also created a shared blog to cover the topics of food, sports, and holidays and celebrations, said Ms. Anderson.

Still, even though the pilot was mostly successful, it ran into some technological challenges, she said.

Jane Sutterlin, an instructional technology specialist for the school who helped with the project, said that “we struggled with sharing files and communicating back and forth.” For instance, the students and teachers originally hoped to exchange video files, but quickly found that those files were too big to send back and forth easily.

Ms. Sutterlin said she was surprised by how much more tech-savvy American students ended up being than the Chinese students.

“I just assumed the [technology] skills of the [Chinese students] would be the same, but they’re not really used to working in groups and collaborating [with technology],” she said.

Learning to Collaborate

Improving those skills in Chinese students was one of the major motivations for undertaking the project, said Zhijian Fang, the principal of the Beijing Yu Yuan Tan Middle and High School, through translator Lin Zhou.

“Our students need to have a digital mind,” he said. “They need to know how to use the Internet, digital media, and media environments to collaborate with each other.”

The Greenleaf exchange program is a needed departure from the longtime teaching methods in Chinese schools, Mr. Zhijian said.

“Traditionally, in China, the instructional method is really teacher-centered. The teacher gives instruction, and the main activity for the student is listening to the teacher’s instruction,” he said. “Also, traditionally, Chinese students tend to learn independently, [not in group collaboration]. This project really breaks that.”

In addition to challenging established teaching methods, the project gave students a chance to see the world from a new perspective, he said.

“Before, [Chinese] students could only look at things from their own perspective. But now they can look at things from different perspectives,” he said.

Beyond those benefits, Mr. Zhijian said, the Chinese students also had a chance to practice their English in a real-world situation.