At a time when many students around the country pride themselves on their political engagement, Iowa teenagers are in a unique position.

The Midwestern state has long fought to maintain its position as first to weigh in on the presidential primary contest, arguing that its small size allows for the retail politics necessary to test the merits of candidates.

The Iowa caucuses—which this year take place Feb. 3—are so decisive that candidates often end their campaigns if they don’t fare well there. And, this year, a new state law will allow more high school students to participate than ever before: 17-year-olds can register to vote and participate in caucuses if they will turn 18 by the general election in November.

More than 5,000 17-year-olds are already registered, said Secretary of State Paul Pate, who is encouraging educators to push for even more youth participation.

“It’s a way to get them fired up, get them in on the ground floor, and hopefully keep them committed in the long run,” Pate said.

But, for a digital-first generation that can be hesitant to even talk on the phone, physically participating in the political process with more-experienced adults can be intimidating.

Caucuses are small gatherings where voters make a case for their favored candidate in person. At Republican caucuses, participants then select a nominee through a blind vote. But at Democratic caucuses, they physically gather in groups with other supporters of the same candidate, taking several rounds to eliminate those with low totals and reorganize into new groups that match their second or third choices until a critical mass forms around remaining nominees.

“I know a lot of people here have pretty strong political views,” said Maddie von Harz, 17, a high school senior from Iowa City, who plans to sit out this year’s caucuses. “But a lot of us think our ideas won’t be looked at the same way when we talk to adults about politics because we are younger.”

Iowa ‘Magic’

Many high school students plan to participate. Some even volunteer for campaigns, passing out caucus-commitment cards in their school cafeterias.

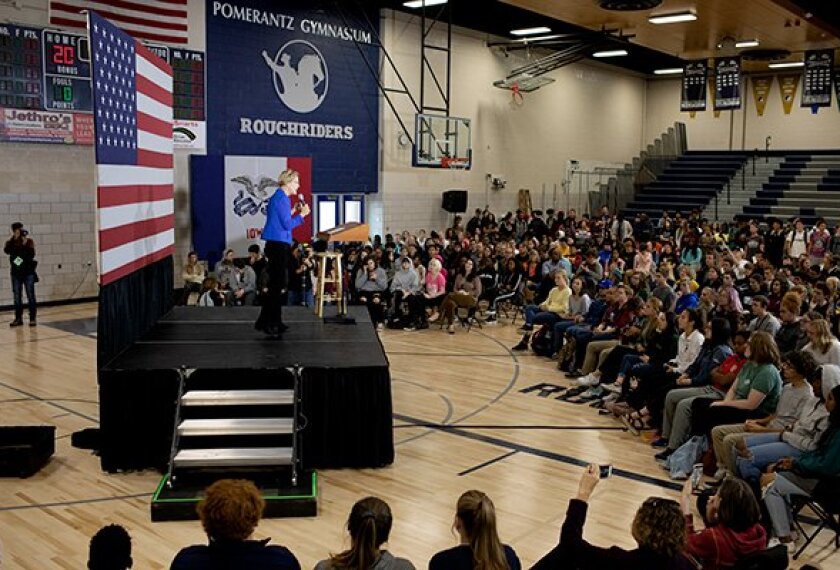

In Des Moines, high school students sparked the creation of a youth-voter forum after they had surprising success recruiting Democratic presidential candidates to speak with their classmates: Six politicians spoke to a crowd of about 500 students at the Sept. 22 event, a school district spokesperson said.

“I did the math,” Democratic candidate Andrew Yang told the crowd, according to the Des Moines Register. “Do you know how many Californians each Iowan is worth? 1,000. ... That is the magic of this state. This is the only place where democracy actually works. And so if you are in this room, you should really caucus.”

For Iowa civics and government teachers, the enthusiasm of an election year—when many Hawkeye State residents can’t go out for a cup of coffee without stumbling into a political event—brings a sense of urgency to prepare the next generation of caucusgoers by helping them understand the history of the event, how to critically process political media coverage and campaign materials, and the steps necessary to participate.

“The responsibility to me is huge,” said Gary Neuzil, who is in his 34th year of teaching government at Iowa City West High School in Iowa City. “If the students don’t get that empowerment at this age, they may never have it. To see that civic-minded citizen that we want to leave our schools, you really have to present information and to excite the kids in a way that will be consequential for the rest of their lives.”

Neuzil encourages eligible students to caucus and those who are too young to attend and observe. Throughout campaign season, he puts candidates’ photos on a screen in the front of the class, discusses major policy and political pronouncements, and plays clips from debates, inviting students to weigh in on their impact.

To help students learn about political messaging, Neuzil makes goofy campaign materials and magazine covers for his own fictitious presidential campaign, inviting them to analyze what works and why. “Do corduroy suits really belong in the White House?” reads a mocked-up Time magazine cover bearing a dated portrait of a young Neuzil. Making himself the center of a joke helps students analyze the ideas, rather than focus on their interest or distaste for any actual candidates, he said.

Voter Uptick

Despite obvious enthusiasm and emerging youth political movements—l����� March for Our Lives, which pushes for new gun laws, and the Sunrise Movement, which advocates policies to address climate change—national data show young Americans are less likely to vote than their older peers, but youth voting interest grew in 2018. That’s true in Iowa, too.

Data that Pate, the secretary of state, analyzed after the 2018 midterms suggests an uptick in voter participation across the board, including among the youngest registered Iowans. About 40 percent of registered Iowa voters ages 18 to 34 participated in the 2018 general election, a rate that hadn’t surpassed 30 percent since the 2002 midterms, Pate reported. Still, only about 38 percent of registered 18- to 24-year-olds voted, compared with 72 percent of voters ages 50-64.

To encourage increased participation, especially among newly eligible 17-year-olds, Pate’s office launched an award program this year for high schools that register at least 90 percent of their eligible students.

U.S. public education is rooted in the belief by early American leaders that the most important knowledge to impart to young people is what it means to be a citizen. If America is experiencing a civic crisis, as many say it is, schools may well be failing at that job.

This article is part of an ongoing effort by �����ܹ���̳ to understand the role of education in preparing the next generation of citizens. For more stories in the Citizen Z series, click here.

Neuzil has used his school’s voter-registration drive to help students understand the individualized ways campaigns reach out to voters. His government class has organized a targeted campaign to reach eligible students. Rather than sending out uniform notes, the students suggested identifying peers in their existing social networks to make their messaging more effective.

When multilingual junior Lilian Montilla, 16, suggested reaching out to Spanish-speaking classmates with notes in their first language, it opened up a classroom conversation about appealing to Latino voters. Neuzil asked students to reflect on former Texas congressman Beto O’Rourke’s use of Spanish during an early debate in the 2020 campaign cycle and on the first Spanish-language presidential campaign ad in the United States, recorded in 1960 by Jacqueline Kennedy on behalf of her husband John F. Kennedy’s campaign.

Lilian’s parents, who immigrated from Venezuela, would find meaning in Spanish-language materials, she said, drawing parallels between her family and her fellow students.

“We have a really big [English-language learner] program here, and they can feel some alienation from the school,” she said.

Lowering Barriers

In addition to registration efforts, schools and communities can encourage turnout by addressing common barriers that keep young voters from participating, says the Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning and Engagement at Tufts University, known as CIRCLE. In an October 2018 poll conducted by CIRCLE, 59 percent of 1,100 18- to 34-year-olds surveyed said they don’t believe election workers make an effort to ensure that “people like them” can vote. Thirty-nine percent of respondents said they didn’t know where to vote, and 26 percent said they needed help discerning the difference between truth and “fake news.”

In Iowa, a panel of social studies and government teachers worked with the secretary of state’s office to create customizable lesson modules and materials called Caucus 101 that are offered free to educators throughout the state. Those lesson plans include mock caucus exercises to help students understand the nuts and bolts of participating.

To avoid spirited discussions of particular candidates, some teachers ask students to caucus for their favorite pizza toppings or cookie flavors. But Jack Vanderflught, a government and history teacher at Dallas Center-Grimes High School northwest of Des Moines, who is also his county’s Republican Party chairman, uses real candidates from both parties in the exercise, sometimes bringing campaign representatives to visit his class.

“They get more excited about it when it seems more personal to them,” he said.

Vanderflught also requires his students to participate in civic activities, like observing public meetings or caucuses or writing letters to public officials.

Caucus lessons happen in the state’s middle schools, too, said Debora Masker, who coaches teachers at Kirn Middle School in Council Bluffs. Masker helps teachers implement new social studies standards that emphasize critical thought and social responsibility in addition to geographic and historical facts. She hopes those lessons will help students as they engage in the political process as adults.

“We’re working really really hard on helping them understand what it means to be an informed voter and to push to become involved in things that matter,” Masker said.

Kirn students also join peers from around the state, selecting their favorite candidates in a Youth Straw Poll conducted by Pate’s office. Candidates film video appeals to students to watch before they vote. In a fall contest, students heavily favored President Donald Trump and Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, one of the Democratic candidates.

Another student poll is scheduled for Jan. 28, a few days before the caucus. If candidates fare poorly in that mock contest, they will likely ignore it, Pate predicted. “But if they do well, they run that number pretty high up the flag pole,” he said.

Bird’s-Eye View

When Iowa City junior Holden Logan, 16, first attended a Democratic caucus in 2016, he was surprised at how informal it was. As his parents met with other voters in an Iowa City arena, Holden sat in the balcony and observed from above.

“All of these people kept moving to different tables for different candidates,” he recalled.

Holden’s family moved to Iowa from Montana six years ago. As he’s gotten older, he’s grown more aware of how significant it is that his state weighs in first in electoral contests. Lessons in Neuzil’s class have made Holden more confident about participating when it’s his turn, he said.

As Maddie, the Iowa City senior, has learned more about the political process, she’s also taken on a sense of responsibility as an early participant in presidential elections. She doesn’t plan to caucus unless she feels more confident about one particular candidate.

“I would go if I knew for a fact what I wanted the outcome of the election to be,” Maddie said. “For me, as a young person, I wouldn’t want to go into it without have super strong opinions.”